Categories

Recent Posts

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

Featured

Most Commented Posts

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

19 comments Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

13 comments Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

12 comments The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

12 comments Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

10 comments

Latest Tweets

Featured

-

Kenya: Helicopter crash kills defense chief and nine senior officers

-

4th Cameroon Investment Forum opens in Douala

-

Cameroon doctors flee to Europe, North America for lucrative jobs

-

Dortmund sink Atletico to reach Champions League semi-finals

-

US: Trump media group plans TV streaming platform

-

Cameroon is broken: Who can fix it?

-

Cameroonian beer and soft drinks exports soar by 73% and 46.6% in 2022

© Cameroon Concord News 2024

26, March 2020

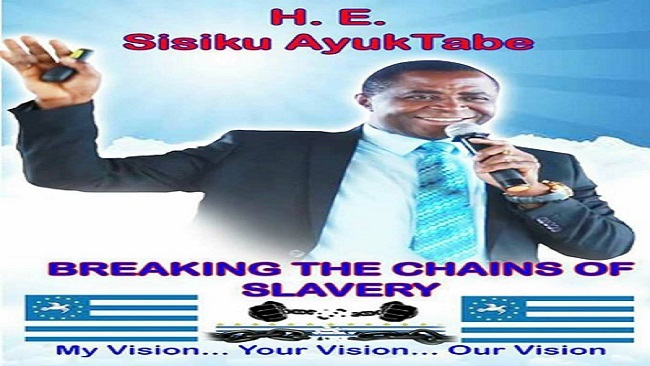

President Sisiku Ayuk Tabe makes public what the people of Southern Cameroons want 0

by soter • Cameroon, Headline News, Politics

“The struggle in Cameroon by the people of Southern Cameroons is not only because the other side is not recognising her system and abiding by the cohabitation principles laid out in 1961, but is also due to the fact that the Republic of Cameroun is completely annexing the British Southern Cameroons, wiping away all signs of its heritage and forcing its people to become the people of the Republic of Cameroun”.

I was going to title this article “What Do Anglophone Cameroonians Want?” To avoid any confusion of identity with those who simplify being Anglophone in Cameroon as being able to speak English, I want to be clear that the claims in Cameroon centre around a people who originate from a specific geographical region known as British Southern Cameroons. In this article, any further mention of Anglophone should be related to people from the then British Southern Cameroons or from West Cameroon, as opposed to anyone from the Republic of Cameroon who can express himself or herself in English. The identity issue is foremost in this struggle. Identity is far more than language. With Identity comes language, values, governance, culture and a way of life. In these aspects, the two peoples in today’s Republic of Cameroon (British Southern Cameroons and the Republic of Cameroun) have fundamental differences. The struggle in Cameroon by the people of Southern Cameroons is not only because the other side is not recognising her system and abiding by the cohabitation principles laid out in 1961, but is also due to the fact that the Republic of Cameroun is completely annexing the British Southern Cameroons, wiping away all signs of its heritage and forcing its people to become the people of the Republic of Cameroun.

2017 offers us a ray of hope, beckoning in the horizon. Our people now have another golden opportunity to decide on divorce from the Republic of Cameroun or to stay in this marriage of convenience and keep complaining. Insanity is doing the same thing and expecting different results. If we do today what our leaders did in 1961 and 1972, then our children, grand children and great-grand children will most likely get in 2083 and 2100 what we have now. The opportunity of this critical juncture cannot be missed!

The world is silent as the time-bomb in Cameroon is ticking to the point of explosion. Even people in neighbouring Nigeria do not seem to know what is happening next door. Hardly does one turn on the TV or the pages of Nigerian newspapers and hear or read anything about Cameroon, in spite of the over 1500 kilometres land border that the two countries share. Nigeria has an embassy and two Consular Offices in Cameroon (Yaoundé, Douala and Buea). Similarly, Cameroon has an embassy in Abuja, a consular office in Lagos and another in Calabar. Estimates put the number of Nigerians living in Cameroon at around two million. What happens in Nigeria has a direct or indirect impact in Cameroon and vice versa. The case of Boko Haram is glaring for all to see. For many people in the world, Cameroon is a country in peace. We should note that peace is not the absence of war. Behind the seeming peace in Cameroon is a growing Anglophone problem; discrimination, marginalisation and almost outright enslavement. This is happening while the world watches in silence. Unfortunately, such problems only come to the limelight when there are strikes, riots and killings.

Recently, the situation in the English speaking part of Cameroon (British Southern Cameroons) could only be described as having been totally dead. The entire Anglophone Cameroon was like a ghost-town. Reports that reached us said that from Ekok and Otu at the southern border with Nigeria, to Afab, Ewelle, Kembong, Mamfe, Batchuo, Bakebe, Tinto, Sumbe, Kumba, Ekondo-titi, Mundemba, Muyuka, Buea, Limbe (Victoria), Tiko, Bamenda, Bali, Wum, Ndop, Kumbo, Nkambe and Menchum, everything was at a standstill. There were no movements, either of people, bikes or vehicles. This was in complete obedience to a sit-in strike called by the Teachers’ Trade Union and the Common-Law Lawyers, following an impasse at the close of last year. The response was even more significant considering the fact that the government of Cameroon deployed ministers and senior administrators to the region, to meet with chiefs and other stakeholders to lobby for the strike not to be adhered to.

In their “quiet” action, the Anglophones had spoken clearly and loudly to the authorities in Yaoundé. There is an Anglophone problem in Cameroon. It should be looked into very carefully and profound solutions sought to it or the people would be left with no alternative than to go their own way. If a marriage cannot work, then divorce becomes the only solution.

Today in Cameroon, we have a situation where teachers of French origin and expression are transferred to the English-speaking part of the country to teach subjects like Biology, Chemistry, Geography, History and Physics. When I was a kid, the only French teachers we had taught us French as a language, which we reluctantly learned. Today, students who study technical education in secondary schools are taught a curriculum that is fundamentally French in nature. As if this is not bad enough, when they complete their studies and have to write the final exams, they write exams set in French. After complaining for many years, the government decided to translate the exams into English and we have ended up now with a situation where a student of Mechanics could see a question set in French as “Quel est le rôle de la bougie dans une voiture?” translated as “what is the role of a candle in a car?” While this translation is correct in verbatim, it is nonsensical in context because of the wrong use of the word “candle” as a translation of “bougie”. The correct translation would have had “spark-plug” instead of “candle”. Little wonder then that Anglophone students are failing exams even before they leave the hall because the right questions were never asked.

The French Law system (Civil Law) is fundamentally different from the British one (Common Law). The educational system in Cameroon today is such that students who go to university to study Law can either end up with a degree in Civil Law or in Common Law. However, there is only one school in Cameroon that trains magistrates and the curriculum of that school is based on the French Civil Law system. What this means is that all the magistrates in Cameroon have been prepared through the French Civil Law system and are expected to go to the English-speaking parts of the nation and adjudicate cases based on the British Common Law order.

There is no Anglophone in any key position in the Supreme Court of the nation. Of the 38 ministers with portfolios in Cameroon, only one (1) is Anglophone. Today, there is no airport in Anglophone Cameroon, but there were three airstrips in this region in 1982. The natural deep-sea port in Cameroon is in Victoria, in the Anglophone region. It has literally been abandoned in preference for the one in Douala, in the Francophone part, which has to be dredged continuously. The only oil refinery in Cameroon is located in the Anglophone part but its taxes are paid to a region in the Francophone part. Over 90 percent of the workers at the oil refinery, from the guards at the gate to the General Manager are Francophones. After a lot of pressure from the Anglophones, the government has been reluctantly creating tertiary education centres in the Anglophone region, but fills them with students of Francophone origin. The latest instance was the admissions into the School of Sports of the University of Bamenda, in the Anglophone part, to which less than five percent of the students are Anglophones. In a class of about 250 students in the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Buea, less than 50 are Anglophones. The situation in the Faculty of Health Sciences at this university is even worse.

To better understand what the Anglophone Cameroonians want, let us take a walk down memory lane and see where they are coming from, why they are here, and where they are going to. The unfortunate situation of Cameroon started in 1919 at the end of World War 1. Before 1919, Kamerun, as it was known, was a German territory. After the war in which the French, British and Belgian forces defeated the Germans, the spoils of war were shared between France and Britain. This was ratified in the Treaty of Versailles. In that agreement, Eastern Cameroon was given to France and Western Cameroon was given to Britain, as Trust Territories. The British government took their part, known as the British Cameroons, and added it to the Republic of Nigeria. Before being attached to Nigeria, Western Cameroon was further divided for administrative convenience into two; Northern British Cameroons and Southern British Cameroons. The Northern British Cameroons was administered as part of Northern Nigeria and the Southern British Cameroons as part of Southern Nigeria.

In 1954, Southern British Cameroons became a self-governing territory, following her declaration of benevolent neutrality in the Nigerian Eastern House of Assembly. It had a governance structure with a legislature, judiciary, House of Chiefs and an executive branch headed by a prime minister. They built a prime minster’s lodge which still stands tall to this day in Buea. They set up democratic institutions in the region and the people there participated actively in a democratic political system. In 1959, multiparty elections were held in the Southern British Cameroons and the opposition party candidate, John Ngu Foncha won and became prime minister, replacing Dr. EML Endeley. A peaceful democratic transfer of power happened in Africa in 1959. Where did we go wrong?

The Unasked Options That Led To a Very Unhealthy Marriage

On January 1, 1960, French Cameroun got its independence from France and named itself the Republic of Cameroun. On October 1, 1960, ten months after the Republic of Cameroun, Nigeria got its independence from Britain and became the Federal Republic of Nigeria. In February 1961, a plebiscite was organised in which the people of British Cameroons (both South and North) were asked to choose whether they wanted to achieve independence by joining the already independent Republic of Cameroun or join the Federal Republic of Nigeria. The people of Northern British Cameroons (part of North-East Nigeria today) voted overwhelmingly to remain as part of Nigeria, while the majority of the people of Southern British Cameroons (today’s Northwest and Southwest regions of Cameroon) voted to join the Republic of Cameroun in a loose confederation. The unasked option was “whether any of the British Cameroons wanted to be an independent nation”. This option would have been in order, considering that the British Southern Cameroons had a land size of about 43,000 km², slightly larger that the 41,543 km² of the Netherlands, with a population of about eight million, more than that of Paraguay.

From July 17 to 21, 1961, the first president of the Republic of Cameroon, Ahmadou Ahidjo, organised a conference in Foumban to draw up a charter for a Two-State system within a federal political arrangement. After the Foumban conference, on September 30, 1961, President Ahidjo proclaimed into being the Federal Republic of Cameroon, and the two states celebrated unification on October 1, 1961. From thence, Southern Cameroons was named West Cameroon and the Republic of Cameroun named East Cameroun. On May 20, 1972, in another master stroke, President Ahidjo outmanoeuvred the people of Southern Cameroons in a stage-managed referendum and created the United Republic of Cameroon. In doing so, he changed the organisation of the Southern Cameroons organisation was earlier divided into six regions (Mamfe, Kumba, Victoria, Bamenda, Wum and Nkambe) into two Provinces of his United Republic; the “South West” and the “North West” Provinces. He divided East Cameroon into five provinces (Northern, Western, Littoral, Central South and Eastern).

How Long? Too Long!

President Ahidjo ruled the United Republic of Cameroon until November 1982, when it is believed that his French doctor tricked him about his health, making him resign and hand over power to his long-time associate and prime minister, Paul Biya. He remained as the president of the only political party at the time, the Cameroun National Union (CNU). It is also widely believed that in 1983, the two powerful men had a feud that led to the former president going into exile in France. In an earlier twist, in June 1983, there was a coup attempt that was foiled. Ahidjo went into exile in July, and in August he announced that he was no longer the head of the CNU. In February 1984, Ahidjo was sentenced to death in absentia for his alleged participation in the failed coup. In April 1984, another violent coup was foiled and many believed that the former president had his hands in it. Ahidjo denied any involvement in the coup. The death sentence on President Ahidjo was later commuted to life-imprisonment by President Biya. Later on Ahidjo moved to Senegal where, on the November 30, 1989, he died of a heart attack in Dakar. In one of my trips to Senegal, I felt truly sorry on visiting and standing beside the tombstone of the man who always coughed before his radio addresses, with every Cameroonian standing still. I read the inscription on his tomb, which translates to “here lies the remains of Ahmadou Ahidjo, the former President of Cameroon”. How and where the mighty fall!

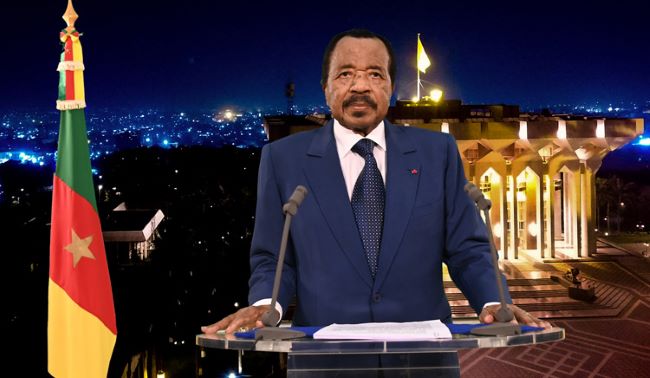

President Paul Biya has been ruling Cameroon since November 1982. Yes, 18 years before the 21st century, 17 years since, and still counting. In 1984, he changed the name of the country from the “United Republic of Cameroon” back to the “Republic of Cameroon”. In the same stroke, he fractured the Northern province into three (Adamawa, North, and Far North). He met a single party in the country and reluctantly accepted multiparty democracy in the early ‘90s, in which he won elections by just over 52 percent. In the last election in 2011, he won by 78 percent. When he took over power, the presidential term of office was without limit. He changed it to two terms of five years each, not counting all the years he had ruled before that date. He changed it again to two terms of seven years, and in 2008 in another constitutional amendment, he eliminated the term limits altogether, making himself practically president for life.

Over the years, most of the people that the presidents of the Republic of Cameroon have placed in key positions in the world’s greatest organisations are Francophones. These include those appointed to the United Nations and key countries, as Ambassadors and High Commissioners. Until 2008, all the Cameroonian Ambassadors to the UN, USA, UK, Nigeria, France and Germany were Francophones. Till date only one Ambassador to these countries, the Cameroon High Commissioner to the UK, is Anglophone.

Cameroon Ambassadors/ High Commissioners to Nigeria (All French-Speaking Cameroonians):

• M. Haman Dicko – 1960 – 1966

• Hamadou Alim – 1966 – 1975

• Mohaman Yerime Lamine – 1975 – 1984

• Souaibou Hayatou – 1984 – 1988

• Samuel Libock – 1988 – 1994

• Salaheddine Abbas Ibrahima – 2008 to date

Cameroon Ambassadors to the United Nations (All French-Speaking Cameroonians):

• Ferdinand Oyono — 1974 to 1982

• Martin Belinga Eboutou — 1998

• Anatole Marie Nkou — 2007

• Michel Tommo Monthé — 2008

Cameroon Ambassadors to the United States of America (All French-Speaking Cameroonians):

• Jacques Kuoh-Moukouri

• Joseph Owono — from 1970s

• Paul Pondi — from 1982 to 1993

• Joseph Bienvenu Charles Foe-Atangana

• H.E. Étoundi Essomba — the current ambassador

Cameroon High Commissioners to the United Kingdom:

• Paul Pondi — 1977

• Dr. Gibering Bol-alima

*Libock Samuel

• Nkwelle Ekaney – 2008 (A English-Speaking Cameroonian)

Cameroon Ambassadors to France (All French-Speaking Cameroonians):

• Ferdinand Oyono — from 1965 to 1968

• Jacques-Roger Booh-Booh — from 1983

• Lejeune Mbella Mbella — over twenty years

• Samuel Mvondo Ayolo — from October 2015

Cameroon Ambassadors to Germany (All French-Speaking Cameroonians):

• Jean-Baptiste Beleoken — 1970’s

• HE Holger Mahnicke

The Anglophone Cameroon problem is real and must be addressed as a matter of urgency.

Sisiku Ayuk Tabe President of the Federal Republic of Ambazonia