Categories

Recent Posts

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

Featured

Most Commented Posts

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

19 comments Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

13 comments Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

12 comments The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

12 comments Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

10 comments

Latest Tweets

Featured

-

Kenya: Helicopter crash kills defense chief and nine senior officers

-

4th Cameroon Investment Forum opens in Douala

-

Cameroon doctors flee to Europe, North America for lucrative jobs

-

Dortmund sink Atletico to reach Champions League semi-finals

-

US: Trump media group plans TV streaming platform

-

Cameroon is broken: Who can fix it?

-

Cameroonian beer and soft drinks exports soar by 73% and 46.6% in 2022

© Cameroon Concord News 2024

20, July 2018

Southern Cameroons Crisis: The dangers of Yaounde-Buea’s war of words 0

FOR decades Cameroon, wedged between central and west Africa, enjoyed a reputation for calm and stability while its neighbours were mired in a cycle of coups-d’état, wars and bloodshed. Yet today that stability is no longer guaranteed, and a long-simmering crisis is erupting. Protests, which began in October 2016 with Anglophone teachers and barristers demonstrating about French curricula and legal texts, have morphed into a conflict of kidnappings, beheadings and the torching of villages. What went wrong?

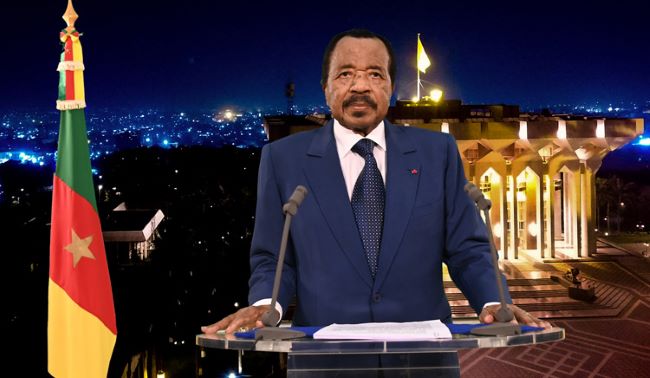

Cameroon was colonised by the Germans in the late 19th century, and after the first world war the League of Nations entrusted the administration of different parts to the British and the French. In 1961, lured by the promise of federalism, the formerly British-held North-West and South-West regions chose to join the newly independent and previously French-held Cameroon. But 11 years later, the country’s first president, Ahmadou Ahidjo reneged on the federalist deal and imposed a unitary state, governed from French-speaking Yaounde. In 1984 the current president, Paul Biya, changed the name of the country to the Republic of Cameroon (the name of the former Francophone territory) and removed from the national flag the second star, which represented the Anglophone regions. The effects are still felt today. Anglophones, who make up less than a fifth of the population, feel marginalised in almost every sphere of life, ranging from the allocation of state resources to political representation.

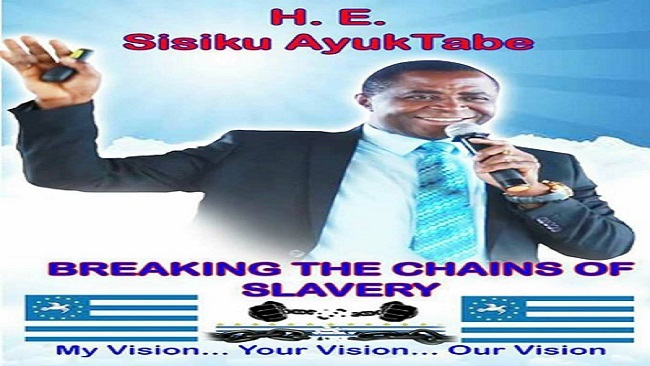

The government reacted to the spreading protests by dismissing the demonstrators as terrorists, throwing their leaders in jail and cutting off internet connections to the two Anglophone regions. This just created more problems. The leadership vacuum was filled by a range of separatist groups, with senior activists ranging from worried men in suits to armed criminals taking advantage of the chaos. Still angered by Ahidjo’s treachery almost half-a-century ago, Anglophones continue to complain that they were not given the option to set up their own state after independence. That has become one of the main demands of some fighters, who declared the establishment of the “Republic of Ambazonia” last October. The crisis has duly developed into a vicious war. Both sides have committed atrocities, but the Anglophones are paying the harshest price. More than 21,000 have fled to neighbouring Nigeria, while in south-west Cameroon entire settlements have become ghost villages, with more than 150,000 people displaced.

Worse, this is just one of three crises facing Cameroon. Northern parts have been affected by the Boko Haram insurgency spilling over from Nigeria. The jihadists’ campaign of suicide bombings and other attacks has forced almost 250,000 Cameroonians to flee their homes and led to the arrival of more than 95,000 Nigerians refugees. At the same time, over 230,000 refugees from the Central African Republic have come to eastern Cameroon, bringing with them a bloody struggle for power and access to natural resources. In the presidential election due for October, Mr Biya—Africa’s oldest ruler at 85—is expected to seek a seventh term in power. Mr Biya has no obvious successor, in a government anchored in sclerosis. Yet stability in Cameroon is vital not only for the region but for Africa at large. It is the biggest economy in central Africa, and for many people in Cameroon, Chad and the Central African Republic, the port of Douala is a life-line. Cameroon’s elite soldiers, arguably the most efficient in the region, have played a crucial role in the fight against Boko Haram and ISIS splinter groups. If Cameroon plunges further into chaos, other countries could be pulled down with it.

Culled from The Economist