Categories

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

Featured

Most Commented Posts

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

19 comments Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

13 comments Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

12 comments The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

12 comments Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

10 comments

Latest Tweets

Featured

-

4th Cameroon Investment Forum opens in Douala

-

Cameroon doctors flee to Europe, North America for lucrative jobs

-

Dortmund sink Atletico to reach Champions League semi-finals

-

US: Trump media group plans TV streaming platform

-

Cameroon is broken: Who can fix it?

-

Cameroonian beer and soft drinks exports soar by 73% and 46.6% in 2022

-

Southern Cameroons Crisis: 2 teachers abducted in the North West

© Cameroon Concord News 2024

30, October 2019

Why has violence increased since Cameroon’s National Dialogue? 0

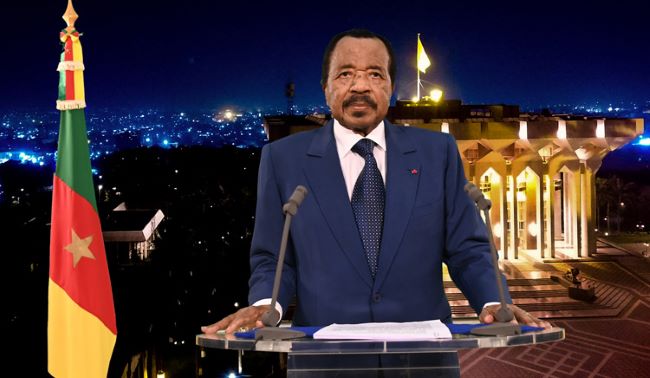

Over the past month, the government of Cameroon has given various indications that its approach to the Anglophone crisis may be changing. After three years of escalating violence, it opened a Grand National Dialogue on 30 September. A few days later, it gave a presidential pardon to over 300 people who had been arrested on misdemeanour charges related to the Anglophone protests. And soon after that, it released several opposition figures including presidential candidate Maurice Kamto who had spent over eight months in prison.

On the surface, these policies suggest a shift in strategy. However, at the same time, the level of violence between the Cameroonian military and secessionist fighters has intensified in recent weeks.

Why is this? Has the government’s approach to the Anglophone crisis really changed?

A new strategy?

The recent actions of President Paul Biya’s administration all bear further scrutiny.

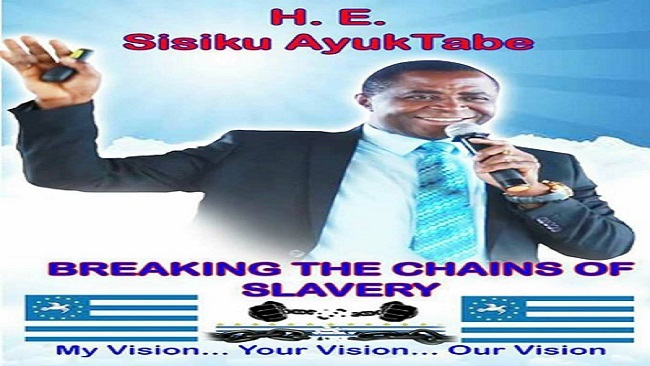

To begin with, the Grand National Dialogue was arguably doomed from the start. Separatists, who have been calling for externally-mediated talks, refused to engage with it from the outset. Many saw the framing of the conference as politically-compromised.

The release of detainees charged with misdemeanours is certainly welcome, but only accounts for a small proportion of those imprisoned. Many more Anglophone activists have been charged with terrorism, a capital offence under Cameroon’s legal code, and remain in jail. Some of those detainees are combatants, but others were arrested for taking part in demonstrations, having “Ambazonia propaganda” on their phones, or on suspicion of cooperating with secessionists. Dozens of separatist leaders arrested in Nigeria in January 2018 also remain locked up in Yaoundé’s notorious Kondengui Central Prison.

The release of Kamto and other opposition leaders should be celebrated too, but it has little to do with the Anglophone crisis. Kamto is a Francophone and was arrested following a presidential election that the secessionists boycotted.

Examining the government’s recent actions in context suggests that its approach has changed far less than it might initially seem. A look at two new strategies of the Cameroon government towards its English-speaking region reinforces this view.

The first is that, following the national dialogue, the government has reshuffled its Divisional Officers (DOs) across the country. Many people in the Anglophone regions perceived the officials in their areas, many of whom were Francophone, to be corrupt. The shake-up may lead to a change of faces, but there is no guarantee that the new ones will be any less corrupt, while they will all still be loyal to the ruling Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM). The same will be true if the heads of state-owned companies or governors are similarly reshuffled as some are expecting. Moving around regime loyalists will do little to address feelings of marginalisation among the Anglophone minority.

The government’s other main new initiative is the establishment of a vigilante and community policing programme in Bamenda, the capital of the English-speaking Northwest Region. The initiative, launched in mid-October, has seen groups of young men being given megaphones, motorcycles and metal detectors. Their primary task is to conduct neighbourhood patrols and alert the army when they come across suspected secessionist fighters. The plan is modelled on a successful initiative in Cameroon’s far north region to fight Boko Haram, though it is notable that those vigilante groups were armed while those as part of the new initiative are not.

This new strategy may have some use, but it highlights the fact that the government continues to see the conflict as a problem of terrorism to be combated with counterinsurgency. This notion is supported by reports that the government is seeking to increase its military capacity in order to attack separatist hideouts. Last week, it purchased advanced artillery from Russia. It has also recently launched offensives that have killed both combatants and civilians. On 20 October, it arrested Paul Njokikang, a Catholic priest and coordinator of the Catholic aid organisation Caritas, causing widespread outrage.

Cameroon seems intent on maintaining its military approach to the crisis even though this has not only failed to stem the conflict but encouraged growing numbers of Anglophones to take up arms.

The secessionists change tack

For their part, the secessionists calling for an independent state of Ambazonia have also been reconsidering their approach. In recent weeks, they have reportedly decided to focus less on international rallies and the lobbying of foreign governments, which have proven largely fruitless. Instead, they seem to be diverting resources to fighters on the ground.

This has already led to a recent uptick in attacks, including one on the convoy of the governor of Northwest region and various military outposts. Militants have reportedly killed a former combatant who laid down his arms as part of a government disarmament programme as well as some members of the new vigilante initiative in Bamenda.

There has also been an increase in unusually brutal violence, some of it targeting civilians. Most shockingly, a video has emerged appearing to show combatants mutilating and murdering a female prison guard. The secessionists claim the act was carried out by government-sponsored actors and that they have captured three individuals behind it, but have not released any further proof. Separatists also kidnapped and tortured a school teacher in the city of Kumba, only releasing her after a hefty ransom was paid. They allegedly maimed employees of the Cameroon Development Cooperation in Southwest Region.

The way forward

The events of the past few weeks make it clear that neither the government nor the separatists plan to change their violent approach to the crisis. In fact, fighting has only increased and the two sides appear as fixed in their positions as ever.

The secessionists insist they will only meet with the government if talks are brokered by a third party such as Switzerland. The government rejects all offers of legitimate mediation. This kind of externally-guaranteed negotiation, however, is the only way out of the crisis. It is the only option to stop the bloodshed and end the spiral. Anything short of this is, at best, window dressing.

Source: Africanarguments