Categories

Recent Posts

- Yaoundé: 4 journalists detained while investigating U.S. deportees

- Ngarbuh Massacre: Rare prison sentences handed to soldiers after killing of 21 civilians

- Ethnic armies and the democratization process in Cameroon: an impediment to democratic consolidation

- AP journalist detained in Cameroon while reporting on U.S. deportees

- Should Pope Leo Visit Cameroon?

Archives

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

Featured

Ethnic armies and the democratization process in Cameroon: an impediment to democratic consolidation

Ethnic armies and the democratization process in Cameroon: an impediment to democratic consolidation  Biya’s message to the Youth on the 60th edition of the National Youth Day

Biya’s message to the Youth on the 60th edition of the National Youth Day  How Cameroon pays the price for disrespecting contracts

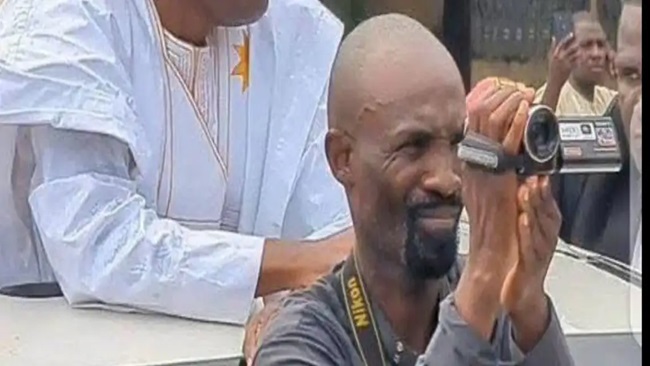

How Cameroon pays the price for disrespecting contracts  Arrest of Issa Tchiroma’s photographer: shameful, disgusting and disgraceful

Arrest of Issa Tchiroma’s photographer: shameful, disgusting and disgraceful  Paul Biya: the clock is ticking—not on his power, but on his place in history

Paul Biya: the clock is ticking—not on his power, but on his place in history

Most Commented Posts

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

18 comments Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

13 comments The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

12 comments Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

12 comments Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

10 comments

Latest Tweets

Featured

-

Yaoundé: 4 journalists detained while investigating U.S. deportees

-

Ngarbuh Massacre: Rare prison sentences handed to soldiers after killing of 21 civilians

-

Ethnic armies and the democratization process in Cameroon: an impediment to democratic consolidation

-

AP journalist detained in Cameroon while reporting on U.S. deportees

-

Should Pope Leo Visit Cameroon?

-

UK: Former Prince Andrew arrested!

-

Murder of 3 Cameroonians: Nigeria police arrest shrine chief priest, 3 others

© Cameroon Concord News 2026

20, February 2026

Ethnic armies and the democratization process in Cameroon: an impediment to democratic consolidation 0

Cameroon presents a compelling case of the complexities surrounding civil- military relations and the democratization process in post-colonial African states. Since independence in 1960, the country has experienced extended one- party rule, contested multiparty reforms beginning in the 1990s, and recurrent tensions between the central government in Yaoundé and various ethnic, regional, and political actors. A key, yet under-mined, dimension of this political trajectory is the role of the ethnic character of the army and how it has functioned as an obstacle to democratic deepening and political liberalization. This article argues that the ethnic configuration of Cameroon’s military establishment has been a significant hindrance to democratization by reinforcing patrimonial state structures, undermining civilian authority, and inhibiting the development of inclusive national institutions. While the literature on ethnic armies and coups in Africa (e.g., Harkness 2006) offers valuable frameworks, Cameroon’s experience highlights how ethnic dynamics within the army interacts with politics, neopatrimonialism, and sociopolitical fragmentation to impede democratic consolidation.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: ETHNICITY, STATE FORMATION, AND THE MILITARY IN CAMEROON

Cameroon’s colonial history-first German under German rule (1884-1916), produced divergence administrative legacies. These legacies have shaped post- independence identities and political structures. The reunification of British Southern Cameroons and French Cameroon in 1961 created a state with significant linguistic and regional cleavages, most notably between Anglophone and Francophone communities. Overtime, these divisions have been translated into political competition and grievances. The Cameroon Armed Forces (Forces Armees Camerounaise, FAC) were establishment under French colonial influence, with early officer corps dominated by recruits from northern and Francophone elite network. This pattern of recruitment contributed to perceptions of the military as an instrument of the dominant political bloc rather than a neutral, national institution. As President Ahmadou Ahidjo consolidated power in the 1960s and 1970s, he used patronage and co-optation to secure the military’s loyalty, embedding ethnic and regional loyalty within military structures. Under Paul Biya, who succeeded Ahidjo in 1982, the military remained an essential pillar of regime survival. Biya’s early purges of Ahidjo loyalists-including army officers from northern and Muslim communities-reinforced the perception of the military as an arena of factional competition. Instead of fostering professionalization and national coherence, the army became increasingly tied to the President’s personal networks and loyalist ethnic/regional blocs, especially those linked to the Beti-Ewondo group from the Centre and South regions. This pattern has important implications for democratization, as outlined below.

A. UNDERMINING CIVILIAN CONTROL OF THE MILITARY

A core prerequisite for democratization is the establishment of civilian supremacy over the armed forces. In Cameroon, the military’s recruitment patterns and internal hierarchies have often reflected ethnic and regional dominance rather than meritocratic professionalism. The privileging of officers from ethnic networks has created informal power centers within the army that are interconnected with ruling party elites. In turn, this undermines the capacity of democratic institutions-parliaments, courts, political parties-to exercise meaningful oversight over security forces. When the military is perceived as loyal to certain elite factions rather than to the constitutional order, it obedience to civilian authority becomes contingent. This conditional obedience weakens democratic accountability and allows the executive to wield the army as a tool of political coercion rather than national defense. An example to substantiate this point was the post election violence that ensued after the proclamation of the October 11, 2025, presidential election result. Several Cameroonians were killed and many were incarcerated by the regime.

B. REINFORCING NEOPATRIMONIALISM AND ELITE DOMINATION

Ethnicized military structures compliment broader neopatrimonial state practices in Cameroon, where political power is centralized around the presidency and distributed through patronage networks. Senior military appointments, promotions, and postings are often used as rewards to loyalists from key ethnic constituencies particularly in the centre and south regions of Cameroon. This practice not only marginalizes other groups but also embeds the military within the executive’s patrimonial rent-seeking apparatus. Accordingly rather than serving as a professional force capable of defending democratic norms and institutions, the army operates as another arena of elite competition and patronage distribution. This undermines the development of autonomous democratic actors and reinforces centralized, authoritarian governance.

C.PERPETUATING ETHNIC AND REGIONAL CLEAVAGES

The ethnicisation of the army has also had indirect but powerful effects on national unity. By privileging certain ethnic groups within military hierarchies, the states reinforce broader social perceptions of exclusion among marginalized communities. This has been particularly salient in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions where perceptions of exclusion from political power and state institutions-including security forces-have fueled long-running grievances and conflict. This dynamics complicate democratization by generating cycles of mistrust, resistance, and militarized dissent. Instead of inclusive dialogue and political participation, dispute over representation and identity are increasingly securitized-a pattern antithetical to democratic deepening.

D.REIFORCING EVIDENCE FROM COMPARATIVE SCHOLARSHIP

The argument that ethnic armies can impede democratization resonates with broader comparative research. Scholars such as Kristen Harkness have shown that the ethnic structuring of security forces in Africa is associated with recurring coups and democratic fragility, as leaders manipulate military composition to secure political survival. In the Cameroon’s case why the military has not staged a successful coup since the early years of independence, its embeddedness within patronage and ethnic networks has nonetheless served a similar stabilizing-yet-anti-democratic function. Rather than challenging the executive through coups, the army’s loyalty is instrumentalized to suppress dissent, reinforce the ruling elite’s dominance, and marginalize alternative political voices. This pattern underscores the need to broaden the concepts of coups to include other forms of military interference that undermine democratic processes.

E. COUNTER ARGUMENTS AND LIMITATIONS

A potential counter argument is that Cameroon’s military has largely abstained from direct political takeover, suggesting a degree of professionalism or restraint inconsistent with ethnicisation. However, this perspective overlooks how the army’s alignment with the incumbent regime functions as a direct impediment to democratization. This absence of coups does not equate to democratic health if military is used to suppress opposition, intimidate civil society, or entrench executive power. Another critic is that ethnic considerations within the army are overstated related to other factors, such as economic incentives, global geopolitics, or institutional weakness. While these factors are undeniably significant, the ethnic dimension in Cameroon amplifies and intersects with them, intensifying the obstacles to democratic reforms.

F. POLICY AND REFORM IMPLICATIONS

It should be worth mentioning that, addressing the impediment of ethnicised military structures requires:

1- A Security Sector Reform (SSR) that prioritizes meritocratic recruitment, transparent promotion systems, and professional training.

2- The reawakening of institutional oversight mechanisms, including strengthening parliamentary committees on defense and ensuring budgetary transparency.

3- The convening of a National Dialogue on inclusion, particularly addressing grievances in Anglophone regions to mitigate the ongoing crisis for close to a decade today and expanding representation within the security forces.

These reforms, while politically challenging, are essential for decoupling the military from elite-ethnic patronage dynamics and enabling democratic consolidation.

CONCLUSION

Using the failed coup attempt in April 1984, to his advantage, Biya then moved forward with discriminatory hiring and promotion policies of his own, within both the civilian government and the military. Over the course of his reign, which continues today, southerners have come to dominate both politics and military (Minority Rights Group 2010). In particular, members of Biya’s southern Bulu group, as well as members of the closely related Beti group, disproportionately hold key positions in the military. Stability was thus re-achieved through renewed ethnic matching policies. Cameroon’s experience demonstrates that ethnicised military structures can constitute a significant obstacle to democratization. By undermining civilian control, reinforcing neopatrimonialism, and perpetuating ethnic cleavages, the army has not only failed to support democratic deepening but has actively sustained authoritarian resilience. Understanding the specific ways in which ethnic dynamics shape civil-military relations is very crucial for both scholarship and policy aimed at fostering democratic transition in Cameroon in particular and across Africa in general

Dr. TARH NTANTANG is the Founder/CEO of Ntantang Research and Consulting Centre (NRCC) in Yaoundé-Cameroon. He is a policy expert and practitioner in democratic support, peace building, and governance with over a decade of experience across Africa. He holds a doctorate in political Economy at the University of Yaoundé 1 and a certified climate migration scholar at York University, Toronto, Canada.