30, September 2019

Grand national dialogue falter as separatists, politicians boycott 0

Government-led talks to end a two-year-old separatist insurgency in Cameroon faltered before they began on Monday as separatists and opposition politicians boycotted the event.

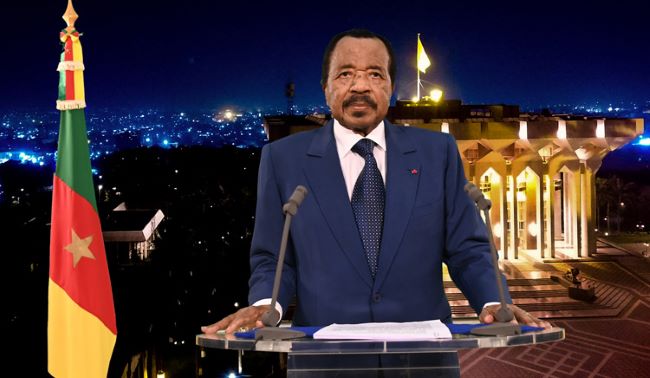

President Paul Biya initiated the week-long national dialogue in an effort to calm violence between militias and the army that has killed more than 1,800 people and displaced more than 500,000, according to United Nations estimates.

But Anglophone separatists, who are trying to form a breakaway state called Ambazonia in the country’s minority English-speaking regions, immediately dismissed the idea because their conditions for dialogue have not yet been met, they said.

“No Ambazonian will take part in Biya’s charade,” said Cho Ayaba, a leading member of the Ambazonian Governing Council.

The council has called for a withdrawal of the army from the English-speaking Southwest and Northwest regions, for international arbitration over the crisis and for the release of all arrested separatists.

Cameroon’s main opposition party is also refusing to attend until the government releases its leader and former presidential candidate Maurice Kamto, who was arrested in January and could face the death penalty for leading protests against an election last year that he denounced as fraudulent.

Biya, 86, won re-election in that vote, extending his nearly four decades in power.

The Anglophone conflict began after the government cracked down on peaceful protests in 2016 in the English-speaking regions by teachers and lawyers complaining that they were being marginalized by the French-speaking majority.

Demonstrators were shot dead and the movement became radicalized. Now at least a dozen groups have taken up arms and have carried out deadly attacks on army posts and the police. The army has responded by burning villages and shooting dead civilians in the English-speaking areas.

Tens of thousands have fled to Nigeria or sought refuge in French-speaking Cameroon.

Opposition parties, civil society groups and representatives of the Catholic Church were present in the main conference center in the capital Yaounde on Monday.

Prime Minister Joseph Dion, an Anglophone appointed early this year in part to jump-start negotiations, was also present.

Dion said the talks were held to end acts of violence and to enable the Northwest and Southwest regions to regain the “necessary serenity”, adding that “all men and women who love peace” had been invited.

Cameroon’s linguistic divide goes back a century to the League of Nations’ decision to split the former German colony of Kamerun between the allied French and British victors at the end of World War One.

For 10 years after the French- and English-speaking regions joined together in 1961, the country was a federation in which the Anglophone regions had their own police, government and judicial system. Biya’s centralization push since he came to power in 1982 quickly eroded any remaining Anglophone autonomy.

Now, moderates who have long called for a return to some form of federal system to ease tensions say their voices have been drowned out by secessionists on one hand and Biya on the other.

“It is farcical to not have a commission to discuss federalism, which is at the core of all this,” said Akere Muna, an opposition politician and former presidential candidate who is participating in the talks. “Now the federalists are a minority and the separatists are the majority.”

By Besong Eunice Nchong

1, October 2019

Inside Southern Cameroon’s 100-year old conflict 0

October 1 marks the second anniversary of the declaration of the “Republic of Ambazonia” for Cameroon’s English-speaking minority.

This year’s anniversary comes one day after a national dialogue to try and end the separatist conflict opened in the capital Yaounde.

the dialogue called by president Paul Biya, who has been in power for 37 years, has been boycotted by key leaders of the separatist movement.

In this article, we trace the roots of the Anglophone conflict in Cameroon, that has now escalated to near-daily clashes between security forces and anglophone separatists.

World War I split

Germany was stripped of its African colony of Kamerun after its 1918 World War I defeat when the League of Nations, the forerunner to the UN, split the territory between victors Britain and France.

Four-fifths went to France, becoming independent Cameroon in 1960.

The British portion, along the border with Nigeria, became independent in 1961. A northern Muslim-majority section chose to join Nigeria while the remaining southern area was unified with Cameroon in a federation.

English-speaking minority

The federal structure was scrapped in 1972 and the anglophone portion was annexed.

Largely francophone Cameroon has 10 regions, two of which are mainly English-speaking: Northwest Region, whose capital is Bamenda, and Southwest Region with Buea as its capital.

They are home to around 14 percent of Cameroon’s population of 23 million.

The two regions are permitted some self-governance and language rights, including bilingual schools. But many complain of francophone-favoured discrimination in education, the justice system and the economy.

Deadly protests

Calls for a breakaway English-speaking state mounted in the 1990s with demands for a referendum on independence accompanied by low-level unrest.

In 2001 secessionists defied a ban on rallies to protest the 40th anniversary of unification with Cameroon and were confronted by security forces. Several people were killed and secessionist leaders arrested.

The separatist Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC) set up a “government” in Britain and leaders moved into exile.

There was a new outbreak of violence in 2016 after lawyers went on strike to demand the right to use Anglo-Saxon common law. Teachers followed, protesting at the appointment of francophones in the region.

While some protesters want only a return to federalism, a minority is pushing for the creation of an independent state called Ambazonia.

Armed revolt

In January 2017 senior secessionist activists were arrested and charged with terrorism and rebellion. President Paul Biya halted their trials in August, apparently trying to calm the situation.

In October 2017 separatist leaders issued a symbolic declaration of independence. At least 17 people were killed in clashes on the sidelines.

Radical separatists took up arms in late 2017, attacking security forces and torching symbols of the administration, such as schools. They also kidnapped police officers, civil servants and businessmen, sometimes foreigners.

‘Civil war’

In April 2018 the main opposition Social Democratic Front (SDF), which defies the separatists, described the violence as “civil war”.

Separatists torched the Northwest Region home of SDF leader Ni John Fru Ndi in October and also kidnapped his sister, who was later released. Fru Ndi was briefly kidnapped twice in 2019.

A US missionary was killed in the unrest in October 2018 and the following month 79 schoolboys were kidnapped in Bamenda but freed two days later.

In December 2018 Biya ordered the release of 289 people arrested in connection with the crisis.

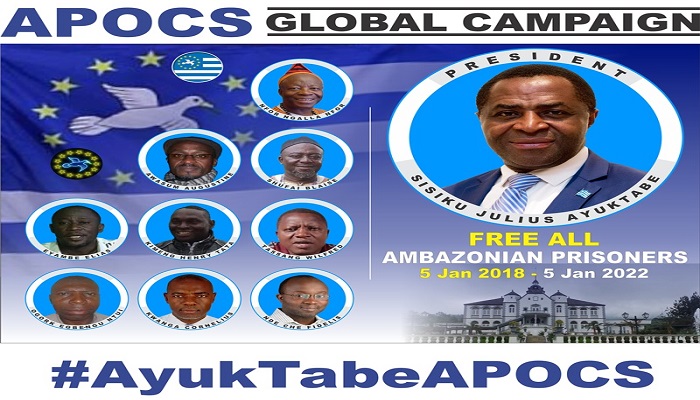

However in August 2019, separatist leader Julius Ayuk Tabe and nine others were sentenced to life in prison for charges including “terrorism and secession”.

More than 2,000 people have been killed in violence between separatists and security forces in the anglophone regions since October 2017, Human Rights Watch says. Around 530,000 have fled their homes, according to the UN.

AFP