12, December 2020

CPDM Crime Syndicate: How much influence do traditional chiefs really have? 0

A growing number of traditional chiefs are occupying leadership positions in government. During regional elections, 20 such chiefs were elected as traditional rulers. However, in reality, their influence has diminished over time.

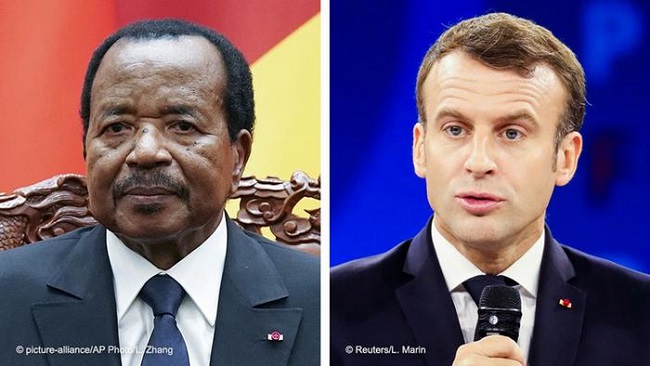

On 2 December, Cameroon’s president, Paul Biya, decided to provide “financial support” to traditional chiefs standing for election as regional councillors on 6 December – a handout that was sure to make waves. The government opted to inform the public of their decision by releasing a statement, a method of communication that exempted its author, the minister of territorial administration, from having to mention the country’s law governing such matters.

As it happens, Cameroon does have a campaign finance law, but it contains no legal provisions concerning the practice of financing independent candidates like traditional chiefs.

Seizing the opportunity afforded by this loophole, the head of state, who also leads the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM) – the ruling party expected to sweep the elections and win the majority of regional council seats – is presenting himself as a benefactor for the “guardians of tradition”.

‘Authentic’ versus ‘administrative’ chiefs

If Biya is pulling out all the stops to remain on good terms with traditional chiefs – leaders who exert an outsize influence over their citizens in the moral and spiritual realm – it is because it is in his best interest to do so. He sees it as an investment and expects to get a good return on investment when these rulers, essentially bound to him, become regional council members.

The highly-centralised Yaoundé government held the regional elections with a certain amount of reluctance. The constitution which provides for such elections came into force 24 years ago, but they were never held before in the country’s history – until this past week.

Be that as it may, on 6 December, each of Cameroon’s 10 regions elected 90 regional councillors, broken down into 70 divisional delegates and 20 traditional rulers.

Under the law, a candidate must be the leader of a first, second or third class chiefdom to be eligible to stand for election: “[…] a first class chiefdom is that chiefdom whose area of jurisdiction covers at least two second class chiefdoms and the territorial boundaries in principle do not exceed those of a division. While a second class chiefdom is that chiefdom whose area of jurisdiction covers that of at least two third class chiefdoms. The boundaries therefore shall, in principle, not exceed those of a sub-division. Meanwhile, a third class chiefdom corresponds to a village or quarter in the rural areas and to a quarter in urban areas”.

Such chiefdom leaders are either monarchs from ancient bloodlines or political dignitaries installed by the administration. Though both categories share the same legal status, the extent of their authority can vary, paving the way for a distinction between “authentic” and “administrative” chiefs.

The shift from a monolithic single-party system to a competitive multi-party system in the 1990s has driven traditional chiefs to flout their duty of neutrality, with most of them choosing to join the ruling party – including the most renowned traditional ruler in the North-West Anglophone region, Fon Angwafo III, whom Biya propelled to first vice president of the CPDM. According to the presidential party’s bylaws, if there is ever a vacancy at the head of the state, the king of Mankon of the Bamenda Grasslands would be sworn into office since, going from second-in-command to top dog, he would become the party’s “default candidate[HE1] ” for the presidential election to be held, as the rules stipulate, within 40 days.

Similarly, if the president of the Senate were to be incapacitated, the election would be carried out under the supervision of the interim president, Aboubakary Abdoulaye. He is the vice president of the upper house of parliament and, as a civilian, the lamido (ruler) of Rey Bouba, the powerful Fula suzerain in the North province of Cameroon.

The Bamum sultan, whose rule extends over more than half of the West region, is a member of the CPDM’s Politbureau and a prominent figure in the Senate, just like the legislative body’s oldest member, Victor Mukete, the supreme leader of the Bafaw people in the South-West Anglophone region.

Carrot-and-stick approach

When they do not hold an elected office, these traditional chiefs turned “auxiliaries of the administration” enjoy other perks from the government. For instance, in accordance with a law enacted in 2013, they receive a monthly allowance from the state of 200,000 CFA francs (first class chiefs), 100,000 CFA francs (second class) and 50,000 CFA francs (third class), or the equivalent of $369, $185 and $92, respectively. This financial assistance costs the government more than 1bn CFA francs each month.

“The regime is trying to rein in traditional rulers and subjugate them. It’s a strategy that helps government leaders retain their grip on power,” says Evariste Fopoussi Fotso, a former national press and communications secretary for the opposition party Social Democratic Front (SDF) and author of the book Faut-il brûler les chefferies traditionnelles ? (published by Editions Sopecam). Faced with the intransigence of opposition leader Maurice Kamto and in an effort to contain his influence, the regime had Max Pokam, the “king” of the Baham people – the community from which Kamto hails – elected.

But the government’s friendly overtures have not wooed every chiefdom, as there are still a few hardliners out there who are keeping Yaoundé’s leaders at a distance. For example, a group of chiefs from the West region published a statement on 19 November that breaks with the regime’s approach to governing. In the text, the authors condemn the ongoing violence in the North-West and South-West Anglophone regions, lambaste the authorities for choosing “the military route” over diplomacy, express concerns about “the widespread loss of trust” alienating politicians from the “people”, call for “the undertaking of electoral reforms” and a constitutional review in order to ensure “stability and the transfer of power at the head of institutions”.

The country’s politicians have little tolerance for traditional chiefs who go against the tide of the political authorities. In December 2019, the government dismissed Paul Marie Biloa Effa, a traditional leader in Yaoundé and special adviser to Kamto. The two regimes that have ruled the country in the time since it was colonised by the German Empire’s Province of Westphalia have taken a carrot-and-stick approach to keeping traditional chiefs at bay.

Colonial legacy

The turbulent relationship between the government and traditional chiefs goes back to the colonial era. The Cameroon of today was a product of the Germano-Douala treaty, an agreement signed on 12 July 1884 by the kings Ndumbé Lobè Bell and Akwa Dika Mpondo, alongside two German representatives, Eduard Schmidt and Johannes Voss. From that moment forward, Germany made a point to make traditional chiefs auxiliaries to the colonial administration, whether by drawing up a treaty or by force.

The colonial leadership planned to subjugate the entire hinterland and impose a system of indirect rule there, in the style of British colonial administrator Lord Frederick Lugard, who had successfully run neighbouring Nigeria in this way. Under such a system, the colonial power could run the conquered country by harnessing the traditional authorities already in place and recognised by the native population.

After the Germans left, the French and British colonists maintained the same policy. Once expansive monarchies, the conquered territories were turned into “traditional communities” that fell under the supervision of administrative districts, known as divisions and sub-divisions, created by the political authorities.

Stripped of their aura and sacred status, kings became “auxiliaries” of the administration, were given a distinct legal status and, as such, subject to the “rights and duties” of their office.

After Cameroon gained independence, these efforts continued under Ahmadou Ahidjo and Biya. To add insult to injury, the latter authorised sub-prefects to establish third class chiefdoms. The ranks of traditional rulers have grown so much that the authority and influence of the most powerful chiefdoms is declining. No doubt the government’s real aim is to rein in the country’s traditional chiefs. That makes it easier to wipe them off the map.

Culled from The Africa Report

14, December 2020

Trump Administration has failed Cameroonian asylum-seekers 0

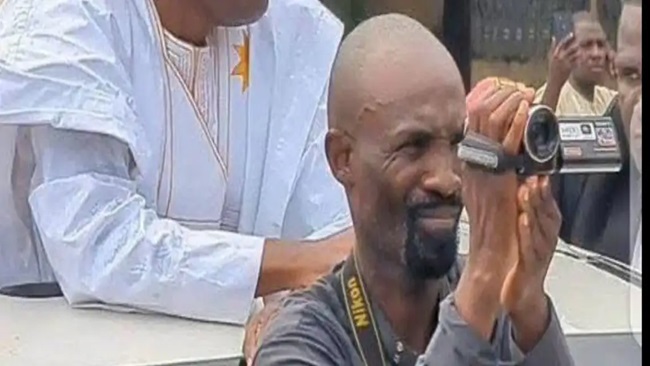

When Franklin Agbor, a former Cameroonian gendarme, disobeyed an order to kill civilians, he was labeled a turncoat. Agbor was patrolling in Cameroon’s Southwest region, which Anglophone separatists regard as part of a breakaway state; his decision not to pull the trigger on behalf of the national government carried a death sentence. With his life in imminent danger under President Paul Biya’s authoritarian regime, the soldier had no choice but to flee Cameroon.

Within weeks, Agbor, 33, left behind his wife and two young children and flew to Ecuador via Nigeria. He traveled up through Central America to Mexico, braving mountains and jungles. Finally, in October 2019, he surrendered himself to the United States for asylum at the Laredo border crossing. Agbor fled to “pursue a brighter future,” said his brother-in-law, Nzombella Atemlefack, who lives in the United States.

But that isn’t what he found. Instead, Agbor spent 13 months in detention at Jackson Parish Correctional Center in Louisiana, denied asylum and parole. His treatment there was “without a conscience,” Atemlefack said. In detention amid the coronavirus pandemic, Agbor faced high-risk conditions—minimal access to medical treatment, no social distancing, no personal protective equipment, and no testing—even as his peers contracted COVID-19. And like other Cameroonian asylum-seekers, Agbor was beaten by immigration officers who forced him to sign his own deportation papers.

Since Cameroon descended into civil war in 2016, more than 400,000 people have fled ethnic and political persecution, with thousands seeking asylum in the United States. Many have instead been detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), suffering conditions that advocates say flout international norms for the treatment of refugees—and reflect glaring inequities for Black migrants in the immigration system. Despite civil demonstrations led by Cameroonians in ICE facilities across the country this year, the poor conditions have only intensified.

The inhumane treatment comes despite the role of the United States in Cameroon’s civil war. In addition to their colonial legacies, Western countries have fanned the flames of the crisis by indirectly bankrolling the persecution of Anglophones with funds for infrastructure and counterterrorism operations. In 2018, while the White House denounced Biya’s administration, the United States donated military helicopters, turboprop jets, and drones to his arsenal. Cameroonians have fled a crisis shaped in part by the West only to be met with hostility on American shores.

Still, those who remain in the United States could be considered lucky. Since October, ICE has deported dozens of Cameroonians: On Oct. 13, 57 Cameroonians were repatriated and handed over to military custody, and on Nov. 11, 37 more—including Agbor—followed. Placed in maximum-security prisons, none has been heard from since, according to families. Several have gone missing. Advocates say another deportation flight is scheduled for Dec. 15.

After the first deportations, several U.S. lawmakers signed letters expressing “grave concerns” over the situation for Cameroonian detainees and ICE’s conduct. In November, Rep. Karen Bass introduced a House resolution demanding an immediate halt to the expulsions and a Department of Justice investigation into the allegations. But as the abuses and the deportations continue, the fate of Cameroonian asylum-seekers shows how the politicized U.S. immigration system has chosen militarization over mercy.

The furor started in Texas. In February, 140 Cameroonian women protested conditions including medical neglect at T. Don Hutto detention center, which has previously come under FBI scrutiny for sexual abuse allegations. Detainees in other facilities soon joined in, galvanized by the potentially fatal consequences of COVID-19. Between March and August, Cameroonians organized hunger strikes against discriminatory treatment and a lack of pandemic precautions in Pine Prairie, a Louisiana facility. In September, Pauline Binam, a Cameroonian woman, was one of the whistleblowers in allegations of forced hysterectomies and other medical abuse while being held at a Georgia ICE facility.

“It seemed like ICE had enough of us,” said Martha Nfonteh, an advocate with the Cameroon American Council whose brother participated in the Pine Prairie protests.

Since the protests, detainees say that things have only gotten worse. Godlove Nswohnonomi, a welder who fled Cameroon in 2018 after getting caught in the crossfire of the conflict, joined the Pine Prairie protests after more than a year in ICE custody—feeling that the poor conditions in the facility put his life “in clear danger.” But he watched as his comrades were pepper sprayed, beaten, placed in solitary confinement, and threatened with deportation. “The way [the ICE officers] looked at us and talked to us, we felt very threatened,” Nswohnonomi said.

Across the country, detainees have experienced a similar pattern of physical violence, emotional abuse, and medical neglect. Of the 23 detainees interviewed by Foreign Policy over the past two months, almost all had similar stories: punishment by ICE officers, the lack of due process, and the inability to seek justice in a court system that appears to be against them. Twelve have since been deported. (ICE officials did not respond to multiple requests for comment on these and other allegations.)

To accelerate these deportations, ICE has used coercive measures to force detainees to sign their own papers—supposedly accepting their deportation before they are expelled. By September, ICE was separating the Pine Prairie protesters, sending them to facilities in far-flung states. Ivo Fogap, who participated in the protests, found himself on a bus to LaSalle, another Louisiana detention facility for those facing imminent expulsion. The bus was packed, and several detainees had symptoms consistent with COVID-19. That’s when Fogap says he understood ICE’s intent: “to put our lives in danger by staying here.”

ICE has a history of medical mismanagement: In 2017, a report by the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General described problems with medical care that “undermine the protection of detainees’ rights, their humane treatment, and the provision of a safe and healthy environment.” “Before COVID, our immigration system had already been making people sicker,” said Amy Zeidan, a physician and co-founder of the Society of Asylum Medicine, which conducts medical evaluations for detainees. “The virus has only made things worse.”

At LaSalle, several individuals were immediately placed in isolation, and the rest were sent to a 70-person dormitory, where many developed high fevers and coughs. One detainee, Valdano Tebid, said he experienced COVID-19 symptoms, but it took six days for him to receive a diagnosis, during which he likely exposed his dormmates. He was released back into the general population after 10 days in quarantine—less time than the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended. Leonard Ataubo, a 23-year-old detainee who was diagnosed with stomach cancer at Pine Prairie, has yet to see a doctor since his diagnosis or begin treatment for the disease, which puts him at high risk of severe illness from COVID-19.

At Prairieland, a Texas facility, detainees report similar conditions. Anonymous callers to a hotline maintained by the advocacy group Freedom for Immigrants have reported that ICE officers have forced them to drink water out of the toilet, punished them in solitary confinement, physically abused them, and denied them adequate treatment for COVID-19. After a transfer to River Correctional Center in Louisiana, Nswohnonomi tested positive for tuberculosis in July, which he believes he contracted while in ICE detention at Pine Prairie. The disease makes him more vulnerable to COVID-19, but he has not received any medicine—a doctor told him he would be deported soon anyway, he said.

The experiences of Cameroonian asylum-seekers reflect broader inequities faced by Black migrants to the United States. Immigration officers have historically used punitive actions, such as solitary confinement, against detained Black migrants at rates up to six times higher than the rest of the population. Likewise, medical mismanagement and neglect may disproportionately affect Black migrants subject to the unconscious biases of medical practitioners.

Despite the extraordinary conditions and health risks, legal recourse has been elusive for Cameroonian detainees. Pandemic-related court closures have delayed and canceled hearings, leaving parole, probation, bond, and humanitarian release out of reach—even for those with conditions that make them more vulnerable to COVID-19 and therefore eligible for release. Officers deemed several detainees simply “ineligible”: Parole was reserved for pregnant women and children or for those with immediate family in the United States, they said—statements that are inconsistent with ICE policy.

Sylvie Bello, the founder of the Cameroon American Council, suspects that there are financial motives for the private corporations that operate the facilities—as well as for the remote regions where the facilities are major local employers and consumers. “Those little itty-bitty Louisiana towns have been profiting off Black bodies from slavery onward,” Bello said. “Immigrant detention is just the latest iteration.”

The detainees’ accounts fit historical patterns. In fiscal 2020, median bond granted to Cameroonians was 25 percent more expensive compared with the broader population facing immigration proceedings. Black migrants are also more likely to face expulsion than other populations in removal proceedings. And in recent months, Cameroonians have increasingly faced other barriers. According to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, the asylum denial rate for Cameroonians has skyrocketed, from around 19 percent in 2019 to around 45 percent in 2020. The deportation rate of Cameroonians has also shot up, from 22 percent in fiscal 2019 to 35 percent in fiscal 2020.

Moreover, advocates fear that ICE has deliberately transferred Cameroonians to antagonistic legal districts. For example, every judge on the immigration court in Jena, Louisiana—with a jurisdiction that stretches across the state—denies asylum at rates of 90 percent or higher. Nathan Bogart, an immigration attorney who frequently works with the court, said that its “harsh” approach symbolizes recent changes that have weaponized Southern courts for deportation. “There have always been questions about whether people of color are treated differently,” Bogart said, citing the court as one reason that Black migrants face an “uphill battle” to asylum.

Calisus Fon, an asylum-seeker detained at the Rio Grande Detention Center in Texas, called the system “pure racism.” His initial credible fear interview—the key step toward asylum—was approved, but over a dozen appeals for his release have been ignored or denied since. Meanwhile, Central American friends in the facility have been granted parole. “All of this effort to send me back home just means they want me to die,” Fon said. “I guess that is why they are treating us how they are here, too.”

On Nov. 11, Fon joined Agbor, Fogap, and dozens of others when he was deported to Cameroon. His pleas to be sent anywhere else were denied. “These people came to America in one piece,” Nfonteh, whose brother remains detained, said. “They are going back broken, body and soul.”

Culled from Foreign Policy