7, June 2018

Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis Intensifies – Why the Central Government Is Ultimately Responsible for Perpetuating the Escalating Violence 0

In the past year, both national holidays commemorating Cameroon’s foundations – October 2017’s independence anniversary and May 2018’s National Day salute to the unitary state system – were marred by violence between the Francophone government and Anglophone secessionists. The secessionists, who formally declared independence for the “Republic of Ambazonia” in October, have struggled to establish a sovereign state comprising the bilingual country’s primarily English-speaking Northwest and Southwest Regions. Now, they are resorting to any means necessary – including violence – to achieve their goals.

Issues of minority recognition in Cameroon are rooted in the country’s post-colonial unification and long-standing tradition of sidelining the English-speaking minority’s language and customs. When the movement’s current manifestation emerged in late 2016, it did so through peaceful protests calling for a return to Anglophone-Francophone federalism. However, because of the government’s violent reaction to such demonstrations, the movement morphed into its present form. It is now more mainstream in reach, but more extreme in strategy.

The shift in the movement’s ultimate goal–from power-sharing to secession–has subsequently changed its methodology. Now, life in the Northwest and Southwest Regions of Cameroon is characterized by fear as protests, curfews, security patrols, arrests, abductions, and killings occur daily. While the rebels’ strategy has become increasingly violent, the central government is equally responsible for the many deaths and disappearances reported over the past six months.

Violence around Cameroon’s May National Day celebrations is a microcosm of the larger conflict. Expectedly, hostility stained the commemoration of the 46th anniversary of the country’s transition from a federal system–which equalized the French and English language, legal, and educational systems–to the Francophone-based unitary state system, approved by national referendum in 1972. While Francophones celebrated the May 20 holiday in Yaoundé with a parade and speeches, Anglophone secessionists boycotted festivities, kidnapped local leaders, and murdered several police officers. Then, later in the week, several dozen so-called “terrorists” were killed by security forces in the Northwest Region. This retaliation not only added to the number of casualties, but also signaled that the government is willing to strike back.

Reports since October 2017 indicate that a high number of civilians and secessionists–allegedly over one hundred– have died in clashes with government troops, in addition to the hundreds arrested. Meanwhile, rebels have reportedly killed at least forty government personnel, and have abducted, held, and tortured scores of local leaders, teachers, government supporters, and security agents.

The fighting has also led to substantial displacement. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, more than 160,000 people have been displaced within Cameroon since 2016. At the end of March, the United Nations Refugee Agency reported that over 20,000 refugees have fled into neighboring Nigeria, with more than half arriving in 2018 alone.

The use of violent tactics by marginalized populations agitating for political rights and representation showcases a systemic problem within authoritarian countries. While many similar movements begin peacefully, brutal governmental reactions often follow. In many cases, governmental overreaction signals that peaceful mobilization will be fruitless and provides an opening for a movement’s more radical members.

In Cameroon, peaceful protests in late 2016 were met with repression, resulting in the existing situation and placing responsibility for the violence squarely on the shoulders of the central government. The government’s violent reaction–coupled with its unwillingness to negotiate with Anglophone leaders or compromise its current policies–forced a subset of the Anglophone movement to conclude that no recourse was available except violence of their own. While it is unclear how representative these violent groups are of the larger Anglophone movement, it is dangerous for anyone in an opposition movement to resort to violence; such a strategy ultimately provides repressive governments an opening to label the entire movement as “terrorists” or “dissidents” and to ignore those peacefully advocating for their rights.

As a result, while there are many Anglophones who sympathize with the movement’s original intent, the violence has created a situation in which citizens are forced to choose: support the Cameroonian state and continue to be marginalized, or support the “Ambazonians” and risk being deemed a terrorist. The high levels of displacement suggest that picking sides is more dangerous than fleeing.

Whether it evolves into a full scale civil war and humanitarian disaster or not, the current conflict triggers questions regarding the legitimacy of the Anglophone movement. Before the movement resorted to violence, the Francophone government’s crackdown on Anglophone protesters was viewed as authoritarian repression against innocent civilians seeking a break from long-standing marginalization. Although peaceful methods did not help them to accomplish their goals, the Anglophone movement’s acceptance of–and explicit call for–violence as a tactic in their struggle against the state may delegitimize their objectives as it displaces and harms innocent civilians. Furthermore, the group’s indiscriminate violence may concurrently provide security forces with an excuse to use similar tactics and legitimize the state’s classification of the secessionists as terrorists.

Despite the Anglophone crisis’ steady intensification over the past eight months, the international community has mostly ignored the growing violence and the government’s role perpetuating the situation. While this may be due, in part, to the myriad humanitarian crises and conflicts in the region, the fact that Cameroon–which has been hailed as one of Central Africa’s beacons of stability despite its authoritarian government and is an important partner in the regional war on terror–is facing growing instability as the Anglophone crisis continues to escalate, is not one that many international partners are ready to acknowledge.

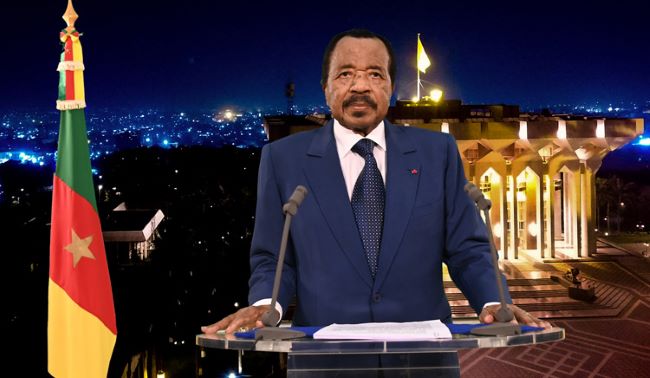

However, in recent weeks, the United States has stepped up, calling for an end to the violence. Following the US Department of State’s Human Rights report’s criticism of abuses in Cameroon, the US Embassy has been more vocal. Prior to Cameroon’s National Day celebrations, US Ambassador Peter Barlerin met with President Paul Biya and explicitly condemned the actions of both sides. While Barlerin denounced the “murders of gendarmes, kidnapping of government officials, and burning of schools” by Anglophone secessionists, he also publicly accused the government of “targeted killings, detentions without access to legal support, family, or the Red Cross, and burning and looting of villages”–an important step in persuading Biya to consider the Anglophone case and reminding the international community that the Cameroonian government is ultimately at fault for the ongoing violence.

Again calling for a dialogue, Barlerin noted that Biya has an opportunity to cement his legacy prior to the upcoming October 2018 elections by re-establishing peace in the country. While the outcome is near certain–Biya will again extend his thirty-five-year hold on power–the elections, which will occur just over a year after “Ambazonia’s” declaration of independence, offer an opportunity for international partners to pressure the government and the secessionists to negotiate peace. In using the leverage gained by supporting regional security efforts, including the fight against Boko Haram, Cameroon’s international partners can persuade the government to end the violence against Anglophones and to seek a long-term solution to their marginalization. Further, the elections provide a national and international platform for the Anglophone movement to amplify its voice and concerns, and to seek the recognition and representation it desires through non-violent means.

Culled from the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center

11, June 2018

Why Akere Muna, the NOW Movement and Joshua Osih will lose the French Camroun 2018 Presidential Elections 0

As it’s often said *’Politics is local’*. It is indeed local.

*Cameroons Electoral Political History*

At the Reunification of Cameroon in 1961, The Southern Cameroons (later West Cameroon) was an electoral Constituency (within which contested the various Southern Cameroons Political Parties).

While LRC (East Cameroon) had three Constituencies that voted along these lines (The Grand North – Fulanis, The Centre South – Betis and the West- Bamileke & Bassa).

*Case Precedent – 1992 Presidential Elections*

The results of the 1992 Presidential Elections displayed the following patterns;

*SDF* – won in the North West, South West, Littoral & West Regions.

*CPDM* – won in the Centre, South, East & Far North Regions.

*UNDP* – won in the Adamawa & North Regions.

Ever since the 1992 Presidential Elections till present, all electoral results have reflected the above patterns.

While the CPDM made inroads into the SDFs & UNDPs Constituencies, both the SDF and UNDP were reduced to Regional Political Parties as seen in the recent Senatorial Elections with the SDF winning only 7 seats of 70 contested seats. While the CPDM won 63 on 70 seats and the UNDP failed to win a single seat.

*Electoral Data*

*SDF*

Looking at the recent Electoral historical data Joshua Osih the SDFs candidate is destined to win less than 15% of the vote. And with Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia his constituency not taking part in the elections, Joshua Osih and the SDF may retain less than 10% of the vote.

*NOW MOVEMENT*

With the *NOW MOVEMENT* taking part in the elections for the first time, not representing any political party and with Ambazonia, Akere Muna’s constituency not taking part in the elections, Akere Muna is destined to win less than 5% of the vote.

*The CPDM*

This leaves the CPDM party and its candidate to win the remainder of the vote with at least 75% and the other 5% being won by other smaller parties like Maurice Kamto’s MRC.

This is based on recent Electoral data in which the CPDM won 56 seats in all 8 Regions of LRC and 7 seats in one of the two Regions in Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia. The above analysis is based on recent empirical data.

*The Wild Card – A Presidential Coalition of Opposition Political Parties/Movements*

Recent electoral data doesn’t prevent the Opposition parties from forming a coalition if they stand a chance of defeating the ruling party CPDM.

Based on recent Coalition Electoral data this coalition will have as members the SDF (Joshua Osih), MRC (Maurice Kamto), NOW Movement (Akere Muna), CDU (Adamou Ndam Njoya), CPP (Kah Walla) and any other smaller political parties.

Of all the above candidates only Maurice Kamto is from LRC and the rest of the candidates are from Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia whose constituency will not be taking part in the elections and whose constituency represent about 20 – 25% of the electorate.

Based on recent Electoral data any coalition will need to win the Grand North constituency (Adamawa, North and Far North Regions) which is currently in the grasp of the CPDM.

It should be noted that the Grand North constituency is the most populated constituency from recent population census data.

The possible best results for any such coalition of Opposition parties will be 20 – 30% of the vote which still leaves the CPDM with an outright victory of 70% of the vote considering Cameroon only conducts a Single round of votes at the Presidential Elections.

*The Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia Question*

With Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia having declared her independence on 1st October 2017 and currently engage in a guerilla warfare with the LRC Military it is difficult to see how up to 20% of the electorate in this part of the country will vote.

Also the Ambazonia Interim Government has prohibited the conducting of any LRC Elections within Ambazonia. The continous displacement of the population of Ambazonia and the reign of terror being executed on these populations by Military Forces from LRC indicates the majority of the populations of Ambazonia are in no mode to take part in elections being organised by a Government who has inflicted so much pain and terror on them.

*Reasons for Outright Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia Restoration of Independence*

The SDF was formed in 1990 with sole mission to restore the former State of West Cameroon. However with citizens from LRC taking much interest in the SDF party, the SDF NEC decided to take a shot at capturing the Presidency of LRC. The SDF candidate at the 1992 Presidential Elections John Fru Ndi came a close second with 36% of the vote, while Paul Biya of the CPDM won with 39% of the votes.

Ever since then the SDF has seen its electoral fortunes reduced and confined to the North West Region giving it a Regional party rather than National party status. This has convinced the majority of Southern Cameroonians/Ambazonians that the only option left to them is to support the Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia Interim Government to enable it restore the Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia’s Autonomy as was the case In 1961.

*Summary*

Based on the above analysis and recent electoral data, it is difficult to assume or predict how either Joshua Osih (SDF) or Akere Muna (NOW Movement) could win the 2018 LRC Presidential Elections.

However in politics nothing is permanent or predictable. I will conclude by stating in October 2018 (that is if the LRC Presidential Elections are held) the results will vindicate the above analysis.

By Oswald Tebit

The opinions expressed here are NOT that of the Cameroon Concord News Group