Categories

Recent Posts

- How Cameroon pays the price for disrespecting contracts

- Yaoundé: Security strains, political tensions cloud potential papal visit

- Eneo Crisis: incessant blackouts in Yaoundé

- France, UK involved in assassination of Muammar Gaddafi’s son

- Cameroon has reached the first 100 days of Biya’s latest term amid ongoing repression

Archives

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

Featured

How Cameroon pays the price for disrespecting contracts

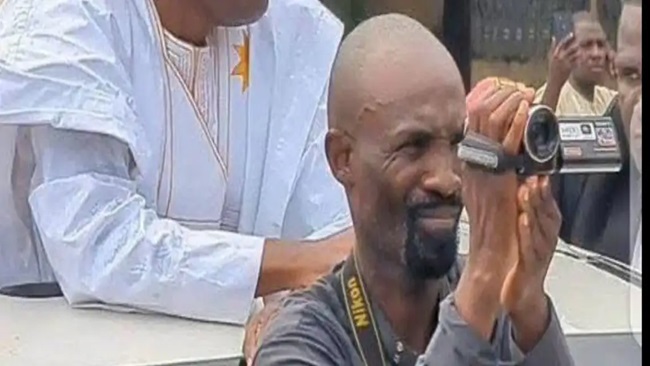

How Cameroon pays the price for disrespecting contracts  Arrest of Issa Tchiroma’s photographer: shameful, disgusting and disgraceful

Arrest of Issa Tchiroma’s photographer: shameful, disgusting and disgraceful  Paul Biya: the clock is ticking—not on his power, but on his place in history

Paul Biya: the clock is ticking—not on his power, but on his place in history  Yaoundé awaits Biya’s new cabinet amid hope and skepticism

Yaoundé awaits Biya’s new cabinet amid hope and skepticism  Issa Tchiroma Bakary is Cameroon Concord Person of the Year

Issa Tchiroma Bakary is Cameroon Concord Person of the Year

Most Commented Posts

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

18 comments Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

13 comments The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

12 comments Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

12 comments Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

10 comments

Latest Tweets

Featured

-

How Cameroon pays the price for disrespecting contracts

-

Yaoundé: Security strains, political tensions cloud potential papal visit

-

Eneo Crisis: incessant blackouts in Yaoundé

-

France, UK involved in assassination of Muammar Gaddafi’s son

-

Cameroon has reached the first 100 days of Biya’s latest term amid ongoing repression

-

SNH reshuffles leadership, names 5 women to senior roles

-

Cameroon sees decline in HIV, women account for most new cases

© Cameroon Concord News 2026

9, February 2026

How Cameroon pays the price for disrespecting contracts 0

by soter • Editorial, Headline News

Contracts are not threats to sovereignty. They are instruments of credibility.

A state that cannot keep its word cannot build an economy. A government that treats contracts as politics invites bankruptcy.

International tribunals ask only one question:

Did the State respect its obligations?

And increasingly, Cameroon is forced to answer:

No

Nkongho Felix Agbor (“Agbor Balla”)

Lawyer and Human Rights Advocate

In Cameroon, public authorities often behave as though contracts are optional documents — instruments that can be suspended, modified, or terminated at will, depending on political convenience or changes in leadership. At home, such decisions may appear cost-free. Officials feel untouchable, shielded by weak institutions, political influence, and a culture of impunity.

But beyond Cameroon’s borders lies a different reality: a global legal system where contracts are enforceable, states are accountable, and breaches are punished not by speeches, but by billions in damages.

Every time Cameroon fails to respect a contract or abrogates one without due process, it exposes itself to international arbitration, costly litigation, massive compensation awards, reputational damage, and long-term economic loss.

And the bill is paid not by ministers — but by citizens.

The International System Cameroon Cannot Escape

Most major state contracts especially in infrastructure, mining, energy, telecommunications, aviation, and public-private partnerships — include international dispute resolution clauses.

These typically refer disputes to institutions such as the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), and the OHADA Common Court of Justice and Arbitration (CCJA).

Once Cameroon signs such contracts, it waives part of its sovereignty. It accepts that foreign tribunals — not Cameroonian authorities — will judge disputes.

There is no political protection at these forums.

No presidential decree.

No “high instructions”.

Only law. Evidence. And consequences.

Practical Cameroonian Examples: When the State Pays

1. The Antonio Conceição Case: Over 1 Billion FCFA

Perhaps the clearest recent example is the dismissal of football coach Antonio Conceição.

After leading the Indomitable Lions to third place at AFCON 2021, Conceição was dismissed without following contractual procedures. FIFA and later the Swiss Federal Tribunal ruled in his favour.

Cameroon was ordered to pay over 1.6 million euros — more than 1 billion FCFA.

The State eventually had to pay to avoid international sanctions.

This was not a football issue.

It was a contract law failure paid from public funds.

2. The Olembe Stadium and Magil: Over 15 Billion FCFA Frozen

The construction of the Olembe Sports Complex in Yaoundé has become a textbook case of how infrastructure contracts turn into financial disasters.

Following disputes with the contractor, Magil Construction, the matter went to international arbitration in Paris.

Cameroon was ordered to deposit more than 15 billion FCFA into an escrow account.

That is 15 billion francs blocked — not for hospitals, not for schools, not for roads but locked in a legal dispute.

3. The SGS Dispute – A Current Risk

Cameroon is currently facing a serious contractual crisis involving SGS, the Swiss multinational responsible for inspection and verification services linked to customs and trade.

SGS operates at the heart of Cameroon’s revenue system.

Recent administrative attempts to suspend or alter this contract without transparent legal process risk triggering international arbitration.

If this happens, Cameroon faces:

• Compensation claims

• Lost profit damages

• Years of interest

• Millions in legal fees

• Possible seizure of state assets abroad

To his credit, the Prime Minister has intervened to seek an institutional solution. This is welcome.

But the SGS episode illustrates a deeper problem:

in Cameroon, contracts are often treated politically first — and legally later.

At international level, SGS is not dealing with a ministry.

It is dealing with the Republic of Cameroon.

And the Republic cannot hide behind circulars.

The Dangerous Illusion of Domestic Power

Cameroonian officials often behave as if:

“What happens in Yaoundé stays in Yaoundé.”

This is false.

A contract signed in Yaoundé is enforceable in Paris, London, Washington, and The Hague.

A minister/Director may feel powerful locally.

But internationally, Cameroon is just another debtor.

Law Is Cheaper Than Arbitration

Good governance is cheaper than litigation.

Dialogue is cheaper than damages.

Due process is cheaper than seizure.

The paradox is brutal:

Cameroon spends more money fighting contracts than honouring them.

Conclusion: Sovereignty Without Law Is Poverty

Contracts are not threats to sovereignty.

They are instruments of credibility.

A state that cannot keep its word cannot build an economy.

A government that treats contracts as politics invites bankruptcy.

International tribunals ask only one question:

Did the State respect its obligations?

And increasingly, Cameroon is forced to answer:

No.

Written and edited by Barrister Agbor Balla