25, February 2025

Jose Mourinho in Turkey: From the Special One to the Crying One 0

Jose Mourinho’s tenure at any club is guaranteed to be colourful, but his eight-month reign as Fenerbahce manager is turning caustic.

The 62-year-old Portuguese has repeatedly revisited his favourite subject of refereeing – an issue Turkish football has struggled with of late – which led to him being accused of racism on Monday night.

BBC Sport breaks down the latest chapter in Jose v Turkish football.

What happened?

Monday’s Istanbul derby between the country’s two biggest clubs Galatasaray and Fenerbahce ended in a not-so-thrilling 0-0 draw – the fireworks coming afterwards in Mourinho’s media conference when he accused the Galatasaray bench of “jumping like monkeys”.

Galatasaray responded by accusing Mourinho of racism – something Fenerbahce deny, with the club’s vice-president insisting Mourinho’s comments were “100% nothing to do with racism. In this situation [Galatasaray are] trying to manipulate simply just resembling [animals]”.

So far, so messy.

Experienced Slovenian referee Slavko Vincic had been drafted in to take charge of the domestic match – the first in nearly 50 years by a foreign official – following a request from both clubs., external

Mourinho thanked Vincic in his post-match media conference for not booking a Fenerbahce player early in the game – believing many refereeing decisions are heavily influenced by Galatasaray.

He then aimed a dig at the Turkish fourth official, in which he is reported to have said: “If you were a referee this match would be a disaster.”

All of which follows months of complaints by Mourinho about officiating in the Turkish Super Lig, including saying he would not have taken the Fenerbahce job if he had known the standards of officiating.

Turkish football’s chaotic past

“The Galatasaray and Fenerbahce derby is the biggest sport event in Turkey,” says Burak Abatay from BBC Turkish.

“Life stops on derby evenings – even the terrible Istanbul traffic is relieved. It is very big tension. The match [last night] was played in this tension.

“There has been a great chaos in Turkish football for a long time. The main discussion is usually about the referees.

“Last season a referee was attacked by a club president in the centre of the pitch. And two teams withdrew from the pitch last season. Another club did the same this season.

“In the middle of this season, foreign referees started to work as VAR referees in all matches, but this did not reduce the controversy.

“President of the Turkish Football Federation Ibrahim Haciosmanoglu stated that the reason for a foreign referee to officiate the derby was ‘to prevent these discussions and not to put the referees in a controversial position’.”

Abatay added: “Galatasaray’s manager Okan Buruk called Jose Mourinho ‘The Crying One’ after the match. He also criticised [referee] Vincic.

“Many football analysts say that Turkish football needs more structural and long-term change.”

And Mourinho’s own club claim change is required, with Fenerbahce vice-president Acun Ilicali claiming there is no protocol for selecting referees in Turkey, “unlike England”.

“In England, if somebody [is] from Newcastle, you cannot be a ref of a Newcastle game,” he told Sky. “[The] problem in Turkey is nobody’s asking referees ‘Which team do you support?’ We don’t know – they can be a Galatasaray fan or Fenerbahce fan.”

Uefa told BBC Sport it “works with its 55 member associations on refereeing”, but the responsibility lies with individual associations to manage the process for its own officials.

In England, professional referees have to declare which teams they support as part of transparency measures – so they avoid games involving their own team.

Is this just more Mourinho antics?

Mourinho is famed for winning some of football’s biggest prizes, all while performing some of the game’s biggest wind-ups.

And while his method of getting under competitors’ skins by criticising referees, managers, players and football authorities has yielded results, it has also formed a questionable reputation in the game’s dark arts.

“Fenerbahce must have known what they were getting into when they hired Jose Mourinho. He is no stranger to headlines,” says BBC Sport chief football news reporter Simon Stone.

“As recently as October, he stated a desire to return to England – and join a club that didn’t compete in Uefa competition as he believed his red card against former club Manchester United was confirmation of an agenda against him.

“The following month he was banned for a game and fined £15,000 by the Turkish FA for an attack on the impartiality of Super Lig officials.

“He maintains to this day his Roma side were badly treated in their Europa League final defeat by Sevilla in 2023, a game when 13 players were booked. Mourinho waited for referee Anthony Taylor in the car park as he was leaving the stadium and expressed his dissatisfaction with the way the Premier League official had handled the game.

“Taylor and his family were subsequently attacked by Roma fans at Budapest airport. Uefa gave Mourinho a four-match ban.”

Culled from the BBC

27, February 2025

Cameroon is currently not high on the US foreign policy agenda—but it should be 0

The country, at the crossroads of Central and West Africa, faces uncertainty across political, social, economic, and security environments. This is happening at a time when the United States’ global competitors are opportunistically seeking engagement in Cameroon and the region, boxing out the United States as it looks to protect its interests there.

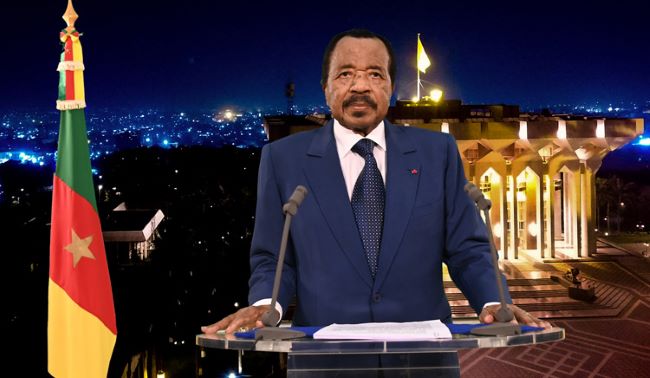

Paul Biya, Cameroon’s ninety-two-year-old leader, has been in power as president since 1982, and from 1975 to 1982, he was the prime minister. Currently rumored to be in poor health, Biya is not seen frequently in public, has little direct contact with US or other foreign officials, and remains relatively recluse. The country faces economic and security challenges despite having a resilient, young population and a capable (yet stretched) military—one with significant experience gained from navigating armed conflict (at home and abroad); counter-piracy, counterterrorism, and peacekeeping, campaigns; and efforts to contain an insurgency in the English-speaking regions of the country.

Biya’s age and the country’s elections, due to be held in October 2025, bring into question what comes next for Cameroon. Navigating the aftermath of Biya’s presidency will require a coordinated and elevated strategic approach by senior US officials. If crisis breaks out in Cameroon, US missteps could play a part in thrusting the country and the region into significant upheaval and instability.

On paper, the president of Cameroon’s Senate, Marcel Niat Njifenji (who was appointed by Biya), would succeed the Cameroonian president in an untimely vacancy. Njifenji—currently at ninety years old and reportedly in poor health—would be tasked with holding elections between 20 and 120 days after the office becomes vacant, as outlined by Cameroon’s constitution. That is a relatively difficult job, even for the nimblest governments. As the ruling political party, the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement and its allies retain all facets of political power in the country. Many key opposition leaders have been divided, fled to self-imposed exile, or have passed away over time. Those in government hold relatively little power for actual change. In recent years, it has seemed possible that Biya would elevate his son as a successor in what has become a trend for the region, but the success of that approach is far from guaranteed.

Absent a unifying leader—one that is unlikely in a country not easily unified by ethnicity, religion, or language—a dangerous and violent scenario could unfold. Acute political instability would unsettle both West and Central Africa and would provide oxygen to armed groups in the Anglophone Crisis as well as in the Chad Basin (where the extremist groups Boko Haram and the Islamic State—West Africa Province are active) and in the porous eastern border with the Central African Republic. Opportunistic criminal networks could exploit any power vacuum in Cameroon and nearby, including next door in southeastern Nigeria.

The question remains: Why should the US government care about Cameroon, a country roughly the size of California with a gross domestic product around the size of Alaska’s, internal and external security issues, and a paralytic gerontocracy? Thus far, despite Cameroon’s strategic location, large economy, and incredible diversity, the United States and Cameroon have been unable to set up a winning partnership that benefits the Cameroonian people. As Cameroon increasingly looks to China as a development partner of choice, the United States should realize that its influence in Cameroon can’t be taken for granted.

US-Cameroon relations have historically been prickly and sometimes even outright rocky. Cameroon has come to distrust the United States after a series of real or perceived slights, including misunderstandings about contested presidential elections in 1992 (that ultimately saw Paul Biya prevail), suspension from the African Growth and Opportunity Act during the first Trump administration, and certain US policy decisions regarding conflict in the Anglophone regions of the country, which led to severe restrictions on US foreign assistance and military cooperation. US-Cameroon relations have also been affected by the fact that a small minority of the Cameroonian diaspora in the United States has engaged in the Anglophone Crisis, including by rallying funding, commanding fighters, and publicly coordinating messaging campaigns for militia groups seeking independence from the Francophone-dominated government. While the US government took some steps to reign in these actions, Cameroonian officials saw extended timelines on the US response and limited results as fundamentally unhelpful. At the same time, some members of the Cameroonian diaspora felt that the US government should have exerted more pressure on both the Biya-led government and armed groups to negotiate an end to the conflict. Back in Cameroon’s capital, the Biya-led government (in keeping with its history as a member of the Non-Aligned Movement) kept its options for international partnership open by engaging with Russia and China, in addition to France, Israel, and the United Kingdom.

From Cameroon’s standpoint, US engagement lacks consistency, seeing as Washington has been one to walk away, reduce foreign assistance programming, or limit security cooperation when Cameroonian human-rights or governance issues (which Cameroon perceives as domestic issues) become bilateral foreign policy irritants. Regardless, US policymakers expect Cameroon to accept the US worldview even if it doesn’t meet the country’s development, security, or economic goals.

One reason the United States should care about Cameroon is because of the country’s role as an economic hub for the region. Cameroon, located on the Gulf of Guinea, connects landlocked Central African countries such as Chad and the Central African Republic to the Atlantic Ocean. Cameroon’s ports at Douala and Kribi (the latter a project under China’s Belt and Road Initiative) provide a significant economic lifeline, facilitating the export of crude petroleum, natural gas, and timber and the import of refined petroleum, food, and clothing. Like many global ports, these port facilities also function as hubs for criminal networks and conflict actors. For example, according to the Africa Report, the Russian paramilitary organization Wagner Group used the port of Douala to enrich themselves and move their assets further inland.

The United States also has an economic interest in a secure and transparent Cameroon. Currently, Cameroon struggles with corruption, although efforts to combat such corruption remain ongoing. A loyalty-based patronage system as well as paper-based procurement processes (through which it is easier to exchange bribes) contribute to this climate. According to the US Department of State, US firms have said that corruption is most pervasive in government procurement, the award of licenses or concessions, monetary transfers, performance requirements, dispute settlements, the regulatory system, customs, and taxation. Efforts to hold officials accountable for corruption are mixed. In 2012, Cameroonian authorities found former Minister Hamidou Marafa Yaya guilty of corruption, but Marafa denied making any attempt at embezzlement and said his detention is politically motivated—and a United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention concluded his detention is arbitrary, saying his right to a fair trial had been violated. In 2023, a Cameroonian court sentenced former Minister of Defense Edgar Alain Mebe Ngo’o, his wife, and three other co-defendants to prison for corruption charges involving military contracts (Ngo’o and his wife denied any wrongdoing).

There is much at stake in Cameroon. Here are ten recommendations for the Trump administration.

Recommendations for the immediate term

Develop a high-level interagency Cameroon strategy. It should include visits by senior US Department of State and other executive-branch officials. This effort can reinforce the work of the US ambassador to Cameroon as a potential crisis looms. In an era of great-power competition, this strategy should include a clear definition of US goals in Cameroon, in addition to a review of the US foreign policy tools available to assist Cameroon with its development, security, and governance challenges.

Intensify engagement and meetings with all parties involved in the upcoming presidential elections. Avoid statements or appearances that could be interpreted as picking potential successors, which were the source of ruffling in the US-Cameroon relationship in 1992.

Focus on creating stronger economic ties with Cameroon while also supporting human rights and good governance. This is what Cameroonian officials tell US officials that they want. Previous US policy reduced economic and commercial ties in Cameroon out of concern for human rights and governance, using standards that may not be universally applied to other non-African countries facing similar challenges. Instead, the United States can push for improved human rights and governance (for example, by advocating for the release of high-profile political prisoners such as Marafa) while also pursuing stronger economic and commercial ties.

Seek wider perspectives beyond government-to-government contact. Engage credible voices on Cameroon in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere in real and consistent policy discussions instead of one-off roundtables that lack staying power and impact. Doing so can ensure that the United States has access to a full range of views about the political process and to networks that the administration can draw upon in a crisis.

Proactively engage congressional leaders and their senior staff on Cameroon matters. This can be accomplished through testimony, hearings, the Congressional Research Service, and other legislative branch tools. Encourage congressional staff and member delegations to Cameroon to inform other congressional staff and members of what is at stake.

Recommendations for the short-to-medium term

Task the intelligence community with assessing the political, economic, social, and security situation in the country. This assessment should outline critical public messaging themes that can help unify Cameroon in a potential crisis, the key players in the country’s future, and potential successors among the political, economic, and military elites. The assessment should include listings of monetary assets, real estate and commercial holdings, and any US dollar-denominated bank accounts. The intelligence assessment should also shed light on money laundering and terrorist financing vulnerabilities for this regional banking hub, and it should map and analyze the relationships key Cameroonians have with Russia, China, and Israel for potential leverage points during a crisis.

Hold a tabletop exercise to plan for realistic political scenarios. The tabletop exercise should include agencies from across the US government and also the US embassy in Cameroon. Such an exercise would help the US government understand what the various scenarios mean for US personnel, Peace Corps volunteers, and US facilities in the country. In Cameroon, most official US personnel and facilities are based in Yaoundé, so evacuation may be difficult: While Yaoundé has an international airport, the Cameroonian international airport that offers the most flights and destinations is in Douala, nearly five hours away. Such challenges require early contingency planning.

Learn from past mistakes in Cameroon and more recent ones made elsewhere, for example in Sudan. Political transitions can happen quickly. Ensuring that the US government has a strategy and network to draw from in a crisis or post-crisis scenario can help decisionmakers as they articulate what a positive relationship with Cameroon could look like—potentially with an untested or unknown leader. Doing so may go a long way toward building credibility.

Develop a quick response package. Drawing on an interagency Cameroon strategy, an intelligence assessment, and lessons learned from the past, the US administration should take proactive steps to prepare diplomatic and economic statecraft tools that can be rapidly deployed in the event of crisis. For example, the US administration should consider sanctions targets and be ready to announce them quickly. Government departments and agencies—including State, Defense, Treasury, the Development Finance Corporation, the Millenium Challenge Corporation, and others—should have humanitarian aid, economic support, and incentives for security sector reform ready to deploy quickly in a crisis.

A recommendation for ongoing strategy

Do not wait on traditional allies such as the United Kingdom, France, or others to act in concert. US and ally interests in Cameroon often do not align. France, now on the back foot in several African countries, may not be able to help. Russia and China are in Cameroon for themselves. Global competitors are already aggressively pursuing their political, economic, and security goals in Cameroon.

Cameroon faces an uncertain future. US policymakers have the opportunity to change Cameroon’s trajectory by accompanying the country as it navigates its future uncertainties. Should Cameroon’s future bring wider violence, the potential for the country to fracture around ethnic, linguistic, religious, or other lines could look similar to, or potentially worse than, the break-up of the former Yugoslavia in southern Europe in the 1990s. But if Cameroon can successfully navigate the period ahead with the United States as a viable partner, it will have contributed to stabilizing the heart of Central Africa, building a brighter and stronger future, and keeping US global adversaries at bay.

Source: Atlantic Council