Categories

Recent Posts

- CPDM Crime Syndicate repays CFA39.8bn debt with new borrowings

- Kenya: Helicopter crash kills defense chief and nine senior officers

- 4th Cameroon Investment Forum opens in Douala

- Cameroon doctors flee to Europe, North America for lucrative jobs

- Dortmund sink Atletico to reach Champions League semi-finals

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

Featured

Most Commented Posts

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

19 comments Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

13 comments Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

12 comments The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

12 comments Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

10 comments

Latest Tweets

Featured

-

CPDM Crime Syndicate repays CFA39.8bn debt with new borrowings

-

Kenya: Helicopter crash kills defense chief and nine senior officers

-

4th Cameroon Investment Forum opens in Douala

-

Cameroon doctors flee to Europe, North America for lucrative jobs

-

Dortmund sink Atletico to reach Champions League semi-finals

-

US: Trump media group plans TV streaming platform

-

Cameroon is broken: Who can fix it?

© Cameroon Concord News 2024

22, August 2019

Can the Church help stop Cameroon’s slide into civil war? 0

Last week unidentified gunmen seized two Catholic priests in the village of Ibal in the restive Anglophone region of Cameroon. Church officials said they were “kidnapped late at night” and appealed to their abductors to release them unharmed. Local police claimed that the kidnappers were separatists seeking to break away from Francophone Cameroon and found an independent Anglophone state. But separatist leaders denied that they had taken the priests.

The abduction is just the latest in a series of troubling incidents involving churchmen in the West African country. In May 2017, the body of Bishop Jean-Marie Benoît Balla was discovered in the Sanaga River. The authorities ruled that it was suicide, but local Church officials insist he was murdered. In November 2018, a missionary priest from Kenya was shot dead outside a church in Kembong, in the Anglophone region. Reports suggested that he was killed in crossfire between the Cameroon army and separatists.

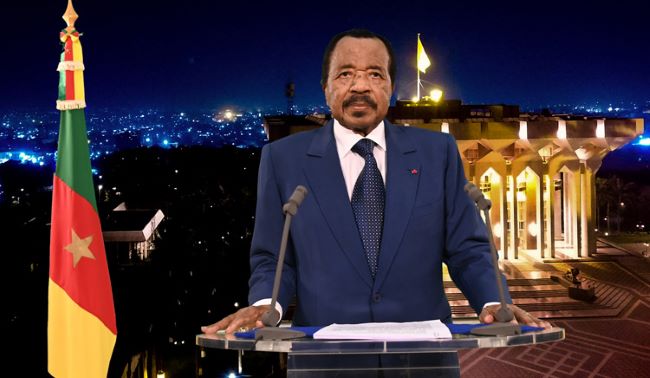

The recent surge in violence has undermined Cameroon’s reputation as one of Africa’s more stable nations. President Paul Biya has ruled the country since 1982. Last year the 86-year-old won a seventh term with a remarkable (some say suspicious) 71 per cent of the votes. But many Western observers blame his refusal to compromise for the worsening conflict in the Anglophone region.

The crisis is rooted in the country’s colonial history. During the First World War, Britain and France combined forces to take over German Kamerun. The Treaty of Versailles gave most of the territory to France. It awarded Britain two small regions next to Nigeria, known as Northern Cameroons and Southern Cameroons. In a 1961 referendum, Northern Cameroons opted to join Nigeria, while Southern Cameroons voted for union with Cameroon, with the assurance that it would have substantial autonomy, including its own prime minister. But in 1972, after another referendum, Cameroon adopted a new constitution which swept away the federal system, replacing it with a unitary state. Southern Cameroons lost its autonomous powers and was divided into two administrative areas, the Northwest Region and the Southwest Region.

President Biya has resisted all appeals to restore autonomy to the Anglophone region. Separatists, in turn, have become ever more vociferous. In September 2017, they declared independence, renaming the Anglophone territories Amazonia and clashing with government forces.

The Catholic Church has a unique role to play amid this conflict, which verges on civil war. The Church is one of the few institutions that truly integrates both French- and English-speakers. Catholics account for 38 per cent of Cameroon’s 20.4 million inhabitants, with Protestants comprising 26 per cent and Muslims 21 per cent, according to the US State Department’s International Religious Freedom Report.

The Church has called consistently for negotiations between the government and separatists. It has suggested that some decentralisation of powers could help to end the unrest. It has also denounced the violence in the Anglophone region. For that, it has paid a price.

In May 2018, shots were fired at the residence of Archbishop Samuel Kleda, president of Cameroon’s bishops’ conference. A local news agency described the incident as an “attempted assassination”. A month earlier, Archbishop Kleda had given a television interview in which he called on the government to make concessions and for both sides to stop the killing. “Since we’re all in the same country and all brothers, our message is to stop the violence immediately at all costs, without vengeance, and accept others who don’t think like us,” he said.

But the fear is that the separatists and the government have moved beyond the point where they can “accept others who don’t think like us” and are engaged in a fight to the death. If this is so, there is little the local Church can do. It will not be able to ensure the safety of clergy in the blood-soaked Anglophone region.

Perhaps it is therefore time for the Vatican to intervene. Biya evidently has a certain respect for the Church. His father was a catechist who hoped his son would become a priest. It was not to be: Biya attended a minor seminary but ultimately left Cameroon to study law in Paris. In 2013, his government signed an agreement with the Holy See outlining the Church’s legal status. If Pope Francis were to invite Biya to Rome perhaps he might be able to persuade him to budge. It seems that no one else can.

Source: Catholic Herald