1, September 2021

University of Buea Sex Scandal: More gory details are emerging 0

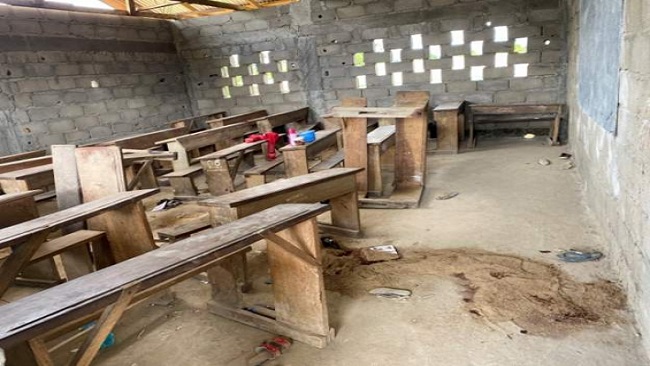

When the University of Buea was created in 1992 by a presidential decree, the country’s English-speaking minority saw only the good side of things. With their usual rose-colored spectacles, English-speaking Cameroonians saw only the bright side and nobody ever thought their beloved university would one day become a place where sex and marks trafficking would take place in plain sight.

But once the university’s doors were opened in 1993, the lecturers, indeed, those who are supposed to guarantee that the sanity and sanctity of the university are intact started demonstrating their ugly side. Those who are supposed to be the custodians of the citadel of learning are clearly failing their students and the entire country’s English-speaking community. The shepherds are all yielding to the temptations of the flesh and the “place to be” has become anything but the ideal place of learning.

The lecturers have transformed the girls into their sex slaves. Sex has been weaponized to dominate the young and vulnerable girls who should be empowered so that they can face the future with confidence and dignity. Almost all University of Buea male staff are involved in the sex scandal. They grant marks to the students and receive free sex in exchange. Many of the students graduate without the requisite knowledge and skills that can make them job-ready.

Many Buea University students and graduates are desperate and for different reasons. The students are desperate because their own lecturers have morphed into a “living terror”. The fear of dealing with a lecherous lecturer has left many students with tons of butterflies in their stomachs. For the graduates, they hold their degrees, but many of those degrees are not even worth the paper on which they have been printed. They are devoid of the knowledge that is supposed to guide them in life. They are bereft of the skills they should have acquired while in the university. They sold sex and got marks but cannot sell the same product to get the job of their dream. Their own lecturers have not only ruined their self-esteem, they have also ruined their chances in life.

The disgraced Prof. Agborbechem and Prof. Ernest Molua are simply the tip of a massive iceberg that might drown the entire university when it melts. The Cameroon Concord News Group has been calling the office of the Vice Chancellor of the University to get his opinion on this issue, but nobody is picking up the calls. Some of the numbers on the university’s letter head simply do not work and nobody has bothered to return our calls. Could the mess flowing all over the university be taking place with the blessing of those who are supposed to check it? Some of the numbers we have used to call the vice-chancellor’s office are: +237233322760, +2372333322134 and 237233322690.

This matter will not be pushed under the rug. The University of Buea cannot be a place where young girls get destroyed by their own lecturers. The Cameroon Concord News Group’s Permanent Correspondent in Buea has been talking with some university students and the outcome of that discussion is a clear indictment of the institution’s lecturers.

Prof. Agborbechem is a champion in this regard and his sins go beyond sex. According to a young student who spoke to our correspondent on condition of anonymity, Agborbechem needs to be fired from that institution. He is a terror that needs to be checked and he should leave with all his accomplices. They are many and if they don’t get checked, they will pull down the entire university. Their usually high and out-of-control libido is a reputational risk to a university that is supposed to be a beacon of hope to the country’s English-speaking minority.

According to a source in the university, “Agborbechem sleeps with female post-graduate students and makes promises to facilitate the defense of their theses. He particularly made such a promise to one post-graduate female student, but when her thesis was taken to the jury, it had so many errors. He had not told the student about those errors. Out of anger, the student promised to expose him for sleeping with her and deceiving her. Agborbechem had to negotiate hard and long for his misconduct and corruption not to be exposed,” the young lady told the Cameroon Concord News Group correspondent.

“As if enough was not enough, he also scheduled a PhD defense when he was not supposed to. He even asks his students to give him money for their defense to take place. For male students, he asks for CFAF 300,000 for them to be scheduled for defense and for the female students who are beautiful, he requests for sex. Those who are not appealing to him must pay the sum of CFAF 200,000,” the student said.

For some time now, the learned but crooked professor has been avoiding motels and hotels for fear that they could be bugged. He has been in this trade for a long time, and he knows the tricks of the trade. His office is now very busy. He is avoiding the watchful eyes of the authorities and those who know him. He has therefore transformed his office into a comfortable motel where he humiliates his victims. He lacks the moral stuff that makes a university don. The university must take appropriate measures to check this satyr who is ruining many lives.

While it is being alleged that the University of Buea is secretly conducting its investigations, the Cameroon Concord News Group is also pleased to inform the public that it has hired some undercover agents to carry out an in-depth investigation into a scandal that is slinging mud at the university’s reputation. The outcome of the Cameroon Concord News Group’s investigation will be published piecemeal.

The Cameroon Concord News Group has nothing against Prof. Agborbechem and Prof. Molua. Its objective is to help the beleaguered university clean up its act. Degrees cannot be obtained on the basis of sex and money. A university is a citadel of learning and the University of Buea was created for that purpose and not for sex.

By Soter Tarh Agbaw-Ebai

Chairman/Editor-In-Chief

Cameroon Concord News and Cameroon Intelligence Report

4, September 2021

Buea University Sex Scandal: The Augean Stable is messy! 0

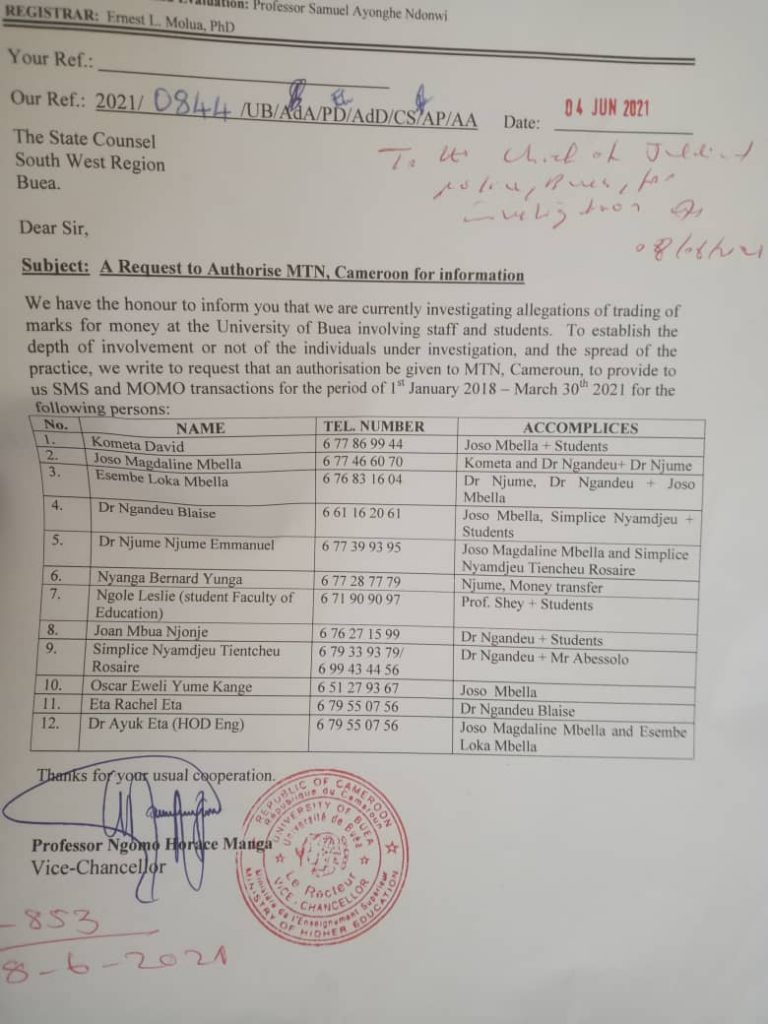

Ever since the University of Buea came under fire because of a sex scandal that is hurting the institution’s reputation, the university’s Vice Chancellor, Prof. Ngomo Horace Manga, has been tight-lipped despite attempts by the Cameroon Concord News Group to obtain his reaction to the mess that might see him out of that institution.

His indifference to the allegations has caused many people in the English-speaking community to think that he might be complicit in the commission of those sex crimes or he could as well be guilty of the same crime. What is Professor Ngomo Horace Manga hiding? Is he trying to protect his accomplices or his protégés?

However, some people hold that the vice chancellor may just be overwhelmed. The Augean Stable is messy. He does not know where to start. When you have people like Prof. Agborbechem and Prof. Ernest Molua to investigate, know that you have a handful. They have had their fair share of the free sex for a very long time in the university and their DNA is all over the hotels in Buea.

For Agborbechem, his crimes are too many. He has been all over the country, and he has been good at sowing his wild oats. Even if you are given the Federal Reserve (American Central Bank) to investigate the learned professor, you will still run out of financially resources. His field of operation is large, and the damage is massive. It is even alleged that even in Nigeria where he studied, he was advised never to return because of his unacceptable sexual escapades.

Speaking to the Cameroon Concord News Group’s Bureau Chief in London, a colleague of Prof. Agborbechem in Fontem, Lebialem Division, was quick to point out that he had never met anybody with such unusually high libido. The professor’s former colleague had little kind words for a man who has projected himself in very bad light because of his out-of-control libido.

“Agborbechem is a polished gentleman when women are not involved. Once he sees a beautiful woman, his brain takes French leave of him. He was very energic when we were in Fontem. The female students in that school should regret having known him. Anything in skirt was good enough for Agborbechem. Make no mistake, he is a very bright person, but when you give him a little alcohol and you throw women in the mix, Agborbechem loses his mind. It is unfortunate that such a learned person could be without self-control,” the professor’s former colleague regretted.

“Many people in Fontem thought he had lost his mind. If he is not mentally messed up, then he has been cursed. How can a man love sex to such ridiculous extents? When he looks at a woman, it is as he should just take her to his bedroom. We used to see him in a strange way, and we thought he had something that was really bothering him,” his former colleague said.

Meanwhile in Buea, many people are still looking forward to a thorough investigation into this sex scandal. Prof. Agborbechem and Prof. Molua have set brand new records when it comes to their sex trade. It is being alleged that sometimes they even tell the girls they want to sleep with to go and rent hotel rooms and only advise them of the transaction for them to come over and accomplish their mission. They not even want to spend a dime in the entire process. This is meanness in its superlative degree.

University of Buea lecturers are really staging a show. Instead of imparting knowledge to those students, they are spending their entire time on women. Some students even argue that some of their lecturers have lost their intellectual edge because they have been discharging their intellectualism into women’s thighs. Rather than spend time conducting research, they spend useful time conducting non-intellectual research in women’s thighs. They love playing the beast with two backs as if that is part of their benefits package.

The University of Buea is an Augean Stable that needs to be cleansed. But it cannot be cleansed by those who are responsible for the mess. Some of the lecturers need to be fired if the mess must be retired. It is time to take the bull by the horn and the vice chancellor must act swiftly and decisively if he really wants to save the university’s reputation or whatever is left of it.

By Soter Tarh Agbaw-Ebai