4, October 2022

Leading Roman Catholic cleric says Amba crisis – now in its sixth year – has become “about money” 0

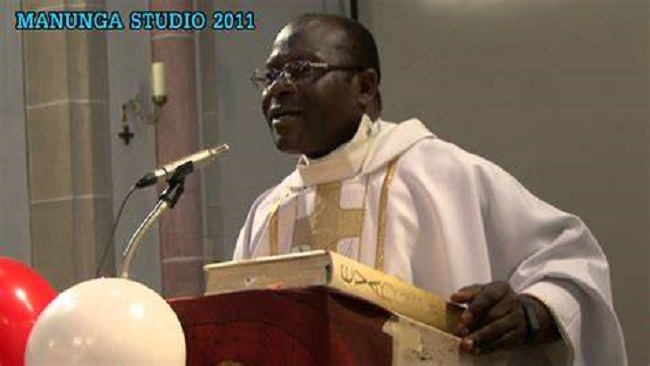

Father Humphrey Tatah Mbuy, the head of the communications department of the bishops’ conference, told a local television station on Oct. 2 that “when money is concerned, it is very difficult to detach a person from his source of income, even if that source is human blood.”

Cameroon is 80 percent French-speaking and 20 percent English-speaking, a result of the country being divided by France and Britain during the colonial era. The two English-speaking North West and South West regions continued to use the British education and common legal systems, but faced marginalization by the Francophone majority for decades.

In 2016, a series of protests by English-speaking teachers and lawyers were violently suppressed by the central government, leading to the present separatist insurgency. So far, over 4,000 people have been killed, and over 700,000 people displaced.

“The conflict…has become what the Frenchman calls ‘L’economie de la Guere.’ It is now a war economy,” Mbuy told the television station.

The priest said the war has turned into a fight for economic benefits, not only by separatists, but by those in government as well. There have been reports of government soldiers arresting people and only releasing them upon the payment of a bribe.

Meanwhile, kidnapping for ransom has become an important way to raise funds for the separatist forces.

On Sept. 16, 30 unidentified gunmen kidnapped five priests, a nun, and three laypeople in the village of Nchang the country’s South West Region.

“The bishop has not been able to get the priests released,” Mbuy said, noting the church has refused to pay the $50,000 ransom demanded by the kidnappers.

The priest said this “war economy” means the parties don’t want to negotiate, making it difficult for the church to work for peace.

Mbuy noted the Catholic Church has played a key role in trying to resolve the crisis from the beginning. In 2016, the bishops of the Bamenda Ecclesiastical Province, which covers the two Anglophone regions, wrote an open letter to the central government tracing the origins of the problem and how best to resolve it.

The priest then lamented the fact that clergy and religious have been targeted in the conflict by both sides, both because of the peacemaking efforts and also for their ransom value.

“This armed conflict in the North West and South West Regions – which should never have been in the first place – is taking on a very wrong approach in conflict management.” Mbuy said.

“You do not touch the person who could help you resolve your problem. If you go for the person who in the end can help you resolve your problem and who has the capacity to help you resolve your problem, then you are shooting yourself in the foot, because the church at the moment, and I can say that without any fear, has the unique moral force to help resolve the armed conflict in the North West and the South West,” he said.

“You can’t force somebody to sit down and talk. You can only discuss with somebody who is ready for a discussion,” Mbuy said.

He also expressed his regret that despite the neutrality of the church, both sides have a history of accusing the church of supporting their opponents. However, the priest reiterated the church’s impartiality in matters of conflict.

“The aggressor and the aggressed are both children of God and the role of the church is that of mother and teacher. When your children are fighting, as a mother you try to bring them together for reconciliation. You do not come as a teacher and take on one side without showing where the truth is. So the church, as a teacher, has to show the truth,” he explained.

Meanwhile, a series of peace marches has been taking place in the capital city Yaoundé to mark the anniversary of the Major National Dialogue that took place Sept. 30-Oct. 4, 2019.

The peace conference resulted in greater autonomy for the Anglophone regions, including the creation of regional assemblies, but separatist groups refused to participate in the dialogue and have not accepted the results.

Source: Crux

7, October 2022

‘We’ve seen God’s miracle within the Southern Cameroons crisis’: Archbishop Nkea 0

Archbishop Andrew Nkea came to the Catholic world’s notice in 2018 at the youth synod in Rome.

Amid much hand-wringing about losing contact with the younger generation, Nkea spoke with refreshing confidence about how parishes in his west-central African homeland of Cameroon were full of young people.

In 2019, Pope Francis named him Archbishop of Bamenda in Cameroon’s Northwest Region. He took up the post as his country was wracked by a conflict known as the Anglophone Crisis, which pitted government forces against separatists intent on creating a breakaway state in Cameroon’s English-speaking territories.

The Catholic Church — which spans the divide between Francophone and Anglophone Cameroon — has suffered amid the complex crisis. Just last month, gunmen seized five priests, a nun, and three lay people at a church in Nchang, a village in Cameroon’s Southwest Region. Pope Francis appealed for their release, but at the time of writing, they remain in captivity.

The Pillar spoke to Archbishop Nkea on Oct. 4, the feast of St. Francis of Assisi. He was visiting the English Diocese of Portsmouth, which is twinned with the Archdiocese of Bamenda.

He discussed the Church’s continued growth, his approach to kidnappers’ demands, and Cameroonian Catholicism’s distinctive features.

Archbishop Nkea, what is Christianity?

Christianity is being like Christ. The name “Christianity” comes from Christ, and to be Christian is to be like Christ. And therefore Christianity is this movement of people who want to become like Christ, that in every day of their lives, they make an effort to be like Jesus Christ.

At a Vatican press conference during the youth synod in 2018, you said: “My churches are all bursting, and I don’t have space to keep the young people.” Has the Church continued to grow in your archdiocese since 2018?

The Church has continued to grow, I would say. You know that we are in crisis in the Archdiocese of Bamenda. But I will say to you without fear or favor that we have seen God’s miracle within the crisis, that our churches continue to be full, the people continue to pray, and the Church is going from strength to strength. Especially with the young people. The young people, despite the difficulties they’re going through, are very committed to their faith.

You said in a Vatican News interview that “the Church in Cameroon is already steeped in the synodal process because of the pastoral plan which we have and in the pastoral plan everything begins from the base.” What is the pastoral plan?

Our pastoral plan is for the whole ecclesiastical province of Bamenda, comprising five dioceses of what we call the Anglophone extraction of Cameroon. In this pastoral plan, we have tried to see, number one, how to consolidate our Christians in the faith and, secondly, how to guarantee a transition of the faith from one generation to another.

One of the things that comes into this pastoral plan is to get the governance of the Church to start from the grassroots and to move up. So, from the families to the small Christian communities, to the mission stations, to the parishes, to the deaneries, before you get to the diocese. And this is the way our Church functions.

Everybody belongs to a small Christian community. And therefore, all the Christians in a particular neighborhood know each other. They have fellowship together. They have small Christian community Masses. And it has built an incredible bond among our people.

That’s why I was saying that we are already within the synodal process, because decision-making begins from the grassroots and the decision is spiraled up to the top, but it must come from the grassroots. Therefore, we don’t take decisions at the top and ram them down the throats of the faithful. But the suggestions come from the bottom and find their way up. And that is how the thing works in Bamenda.

Are small communities different from parishes?

Yes, they are not parishes. Our structure is different. We have parishes and within those parishes, you have what we call mission stations, where the priest goes for Mass, but there is no resident priest there. So there are mission stations, and in those mission stations, there you have small Christian communities. Every mission station has small Christian communities. That will be a group of about five to 10 families within the mission station that kind of take care of each other, watch the back of each other, and that is what it is.

So parishes are not small Christian communities. Small Christian communities are in mission stations. In the little quarters where Christians live, they form small Christian communities, and we call that the Church in the neighborhood.

What activities do the small Christian communities do?

They do Gospel sharing. They teach catechism to their children. And if there’s any fundraising, they do it within the small Christian communities. They accompany those who are bereaved.

It is really important that the Christians feel they belong and they are not isolated when they are in times of joy or in times of trouble, that they have their Christian community as a support. And that is what these small Christian communities are meant for.

The priest only visits them now and again. And this is the important thing, because everything does not depend on the priest. We are trying to make the Church, the Christians, not depend totally on the priest for everything.

For example, if there is a sick person in the community, the small Christian community will visit the sick person and pray with them. And then one of the leaders will inform the priest, who will come for anointing. But the daily visits, or the once-a-week visits, are done by the small Christian community and not by the priest.

You’ve said it’s been difficult sometimes to involve men in the small communities. Why is that?

The men claim to be more busy, and they don’t make time to attend the small Christian community meetings. They want to come once a week to the parish church and attend Mass and go back. Then they have the time to go and watch football or do something else.

But I think slowly, slowly, we’re trying to get the men involved. We have discussed that in our men’s association, to see how to get the men fully involved in the small Christian communities. And in that way, it is the whole family that is involved in the small Christian community: It’s not just a thing for the women and children.

Have you found ways to help men to take part in the communities?

Yes, the Gospel sharing, for example. Reading the Bible and discussing it is not a thing [only] for women. The men just have to develop the interest. From the parish, we send out a text for reflection for the week. And when the men start going, they start finding it very interesting. They don’t stop anymore. They start sharing together. Sometimes when they are sick, they get the whole community coming to visit them and pray with them, and they get more involved. It’s slowly, slowly, but it’s taking root.

Do you have any news about the Catholics kidnapped on Sept. 16 at St. Mary’s Church in Nchang?

We have been talking from time to time with the kidnappers, like I mentioned on the BBC News. They were asking us for money and we don’t have money to give. And even if we had the money, we know that if we start, we’ll never stop. And it’s something we had agreed that we would not do — give money to kidnappers — because then we endanger the lives of all our priests and our Christians.

So they are trying to ask for money. They’ve been negotiating, and going down and down. We are just explaining to them, if you don’t have some food to eat, we can give you some food to eat, but not give you money to go buy guns. The Church can’t do that. So that is where we are: Going forward and backward, trying to get them to understand.

Is there anything else you would like to say?

Yes, I think for one thing, we should all be united in prayer. Today is the feast day of St. Francis of Assisi, who was an apostle of peace. And you discover how much the world lacks peace, how much individuals lack inner peace, how much small communities lack peace. Now we really need to pray for peace, not just peace between fighting and warring nations, but also internal peace for our people. We need to pray.

Secondly, we need to see this thing of Francis of Assisi as personal, because Francis prayed “Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.” It was not to “make us,” and so let us try to see how each individual can contribute. Not to bring war, not to bring hatred, not to bring doubt, but to bring peace, to bring hope, and to bring joy to others. I think this is where all of us as Christians have to look toward one direction.

Culled from The Pillar