Categories

Recent Posts

- CPDM Crime Syndicate repays CFA39.8bn debt with new borrowings

- Kenya: Helicopter crash kills defense chief and nine senior officers

- 4th Cameroon Investment Forum opens in Douala

- Cameroon doctors flee to Europe, North America for lucrative jobs

- Dortmund sink Atletico to reach Champions League semi-finals

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

Featured

Most Commented Posts

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

19 comments Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

13 comments Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

12 comments The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

12 comments Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

10 comments

Latest Tweets

Featured

-

CPDM Crime Syndicate repays CFA39.8bn debt with new borrowings

-

Kenya: Helicopter crash kills defense chief and nine senior officers

-

4th Cameroon Investment Forum opens in Douala

-

Cameroon doctors flee to Europe, North America for lucrative jobs

-

Dortmund sink Atletico to reach Champions League semi-finals

-

US: Trump media group plans TV streaming platform

-

Cameroon is broken: Who can fix it?

© Cameroon Concord News 2024

30, April 2021

Southern Cameroons Crisis: Catholic Bishops criticize violent campaign to quell independence movement 0

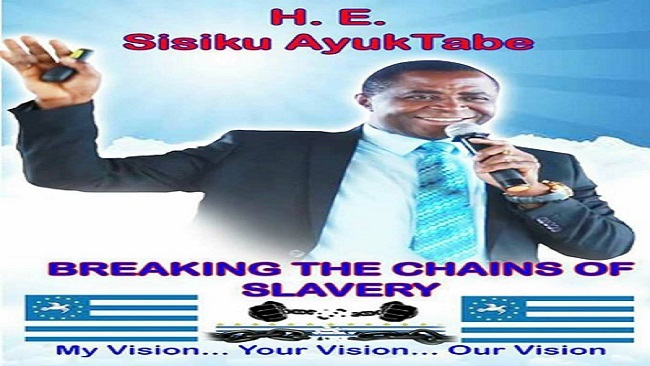

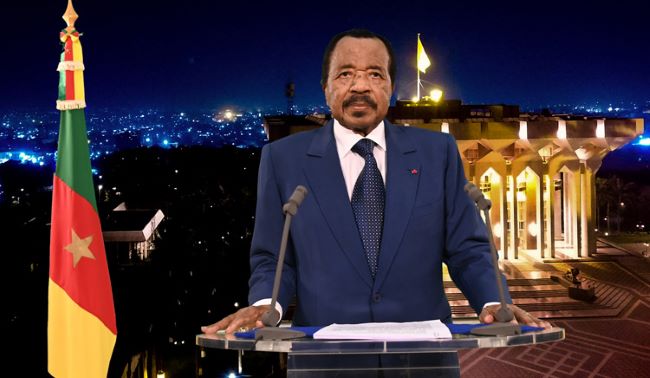

Several Catholic bishops in Cameroon’s English-speaking regions are sharply criticizing President Paul Biya’s violent, years long campaign to quell an independence movement in those regions. In recent NCR interviews, three prelates suggested that Biya’s government had initially underestimated the growing influence of those calling for the creation of a new, separate state and then responded with disproportionate force. Retired Archbishop Cornelius Fontem Esua, who led Cameroon’s Bamenda Archdiocese from 2006 to 2019, said Biya had erred drastically in late 2017 when he pledged to “eliminate” independence fighters. “Violence only begets violence,” Esua told NCR. “The moment the government started using live bullets on peaceful protesters, it was evident that things would simply go out of hand.”

Africa-Cameroon.jpg

Tobin_View_of_the_Cathedral CROP.jpg

Esua said none of these recommendations responds to the demands of Cameroon’s English speakers.

“The whole problem of Cameroon and the sociopolitical situation in the Northwest and Southwest regions is about the form of government. It’s about the two systems of education, it’s about the two systems of law, the two systems of administration. That was not part of the discussion,” the cleric told NCR.

He said he was frustrated that a “special status” for Anglophone regions should even come up as a recommendation, since it’s something already enshrined in the country’s 1996 Constitution.

“It’s not a question of a special status, because it’s not a gift they are giving to the Anglophones. The Anglophones have a right to organize themselves according to their customs and cultures as inherited from the British,” said Esua.

He also blasted the recommendation about hastening the decentralization process, noting that it was paradoxical that the government keeps the centralized structures in place and continues talking about decentralization.

“I’m afraid they are not giving the right solutions to the problem,” said the retired archbishop.

Culled from ncronline.org