21, April 2021

Chad: Mahamat Idriss Deby, son of slain president, emerges as new strongman 0

The youthful general Mahamat Idriss Deby, who stood watch over his late father as head of the presidential guard, is set to take over as Chad’s new head of state, according to a charter released Wednesday by the presidency.

The presidency moved swiftly to put the reins of power in the hands of the 37-year-old general and tear up Chad’s constitution, establishing a “Transition Charter” that lays out a new basic law for the desert country of 16 million people.

The new charter issued Wednesday proclaimed that Mahamat, a career soldier like his father, will “occupy the functions of the president of the republic” and also serve as head of the armed forces.

Mahamat had already been named the head of a military council on Tuesday soon after the announcement of Deby’s death in combat, a move that sidelined other political institutions in Chad and has been branded a coup d’etat by opposition groups.

The four-star general was not on any list of heirs to the throne drawn up by experts, who said they believed the veteran warlord and president had not chosen a successor and seemed to worry little about it.

But Mahamat immediately took charge of a transitional military council and appointed 14 of the most trusted generals to a junta to run Chad until “free and democratic” elections in 18-months time.

Commander in chief of the all-powerful red-bereted presidential guard or DGSSIE security service for state institutions, he carries the nickname Mahamat “Kaka” or grandmother in Chadian Arabic, after his father’s mother who raised him.

“The man in black glasses”, as he is known in military circles, is said to be a discreet, quiet officer who looks after his men.

A career soldier, just like his father, he is from the Zaghawa ethnic group which can boast of numerous top officers in an army seen as one of the finest in the region.

“He has always been at his father’s side. He also led the DGSSIE. The army has gone for continuity in the system,” Kelma Manatouma, a Chadian political science researcher at Paris-Nanterre university, told AFP.

However over recent months the unity of the Zaghawas has fractured and the president has removed several suspect officers, sources close to the palace said.

Born to a mother from the Sharan Goran ethnic group, he also married a Goran, Dahabaye Oumar Souny, a journalist at the presidential press service. She is the daughter of a senior official who was close to former president Hissene Habre, ousted by Idriss Deby in 1990.

The Zaghawa community thus look with some suspicion on Mahamat, some regional experts say.

Challenges ahead

“He is far too young and not especially liked by other officers,” said Roland Marchal, from the International Research Centre at Sciences Po university in Paris.

“There is bound to be a night of the long knives,” Marchal predicted in an interview with AFP.

The rebel forces who have been blamed for Deby’s death have also vowed to press on with their offensive, categorically rejecting the transition of power.

“Chad is not a monarchy,” said a statement from the group known as the Front for Change and Concord in Chad. “There can be no dynastic devolution of power in our country.”

Brought up by his paternal grandmother in N’Djamena, Mahamat was sent to a military lycee in Aix-en-Provence, southern France, but stayed only a few months.

Back home in Chad, he returned to training at the military group school in the capital and joined the presidential guard.

He rose quickly through the command structure from an armoured group to head of security at the presidential palace before taking over the whole DGSSIE structure.

Mahamat was acclaimed for his efforts at the final victory in 2009 at Am-Dam against the forces of nephew Timan Erdimi’s forces. Those forces had launched a rebellion in the east and had reached the gates of the presidential palace a year earlier, before being pushed back after French intervention.

He finally moved out of the shadow of his brother Abdelkerim Idriss Deby, deputy director of the presidential office, when he was appointed deputy chief of the Chadian armed force deployed to Mali in 2013.

That brought Mahamat to work closely with French troops in operation Serval against the jihadists in 2013-14.

“It is hard to imagine France allowing the country to slip into chaos and not supporting Deby’s successor,” regional specialist Vincent Hugueux told FRANCE 24, stressing Chad’s crucial role as France’s main ally in the fight against jihadist insurgents in the wider region.

The French presidency has announced that President Emmanuel Macron will attend Deby’s state funeral on Friday.

(FRANCE 24 with AFP)

22, April 2021

UN: Southern Cameroons lives should matter too 0

The treatment of black people, particularly by law enforcement, has become a principal point of protest in the western world. But little is said about the millions of black Africans mistreated by the ruthless security forces of authoritarian African regimes. If black lives matter regardless of where they are in the world, then it’s time to challenge the immensely privileged black African ruling elite that clings to power by persecuting its often-voiceless black African citizens.

The numbers tell the story. An estimated 5.4 million people or eight percent of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s population died in the 1997-2003 conflict at the hands of government security forces and non-state armed militia. DRC’s violence continues today, barely rating a paragraph in newspapers.

In Sudan, at least 12 percent of the population has died, mostly killed by the security forces of governments recognized and financially supported over the decades by wealthy nations (Two million in Sudan 1983-2005; 400,000 in Darfur; 382,000 in the South Sudan civil war). In Mozambique and Ethiopia, eight percent of the population at the time probably died in each country during the Cold War and its aftermath. In Uganda, Obote and Amin consigned seven percent of their people to a premature death. These are estimates because black African lives matter so little to those in charge, or the international community, that in most cases, no one is keeping count.

Now, it is the turn of Cameroon to be ignored. The Norwegian Refugee Council has described the devastation in this central African nation as the world’s most neglected displacement crisis for the second year running.

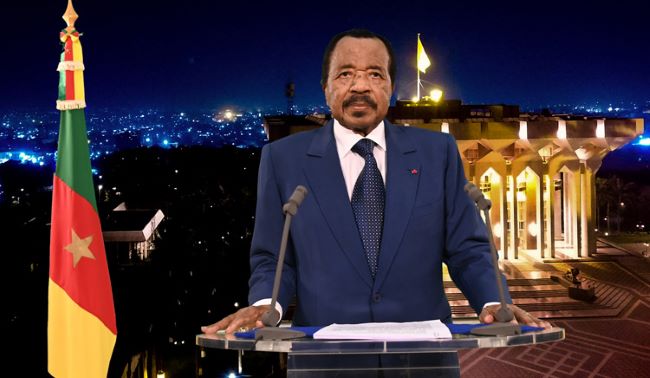

Cameroon has been ruled by President Paul Biya, age 88, since 1982. He continues to win elections that no international monitor considers free and fair. His country is ranked among the world’s most corrupt and repressive by Transparency International and Freedom House, respectively.

In 2016, Biya’s Francophone-dominated regime tried to impose French-speaking judges and teachers on the English-speaking regions, representing 20 percent of the population. The peaceful protests of Anglophones, proud of their Anglo-Saxon courts and schools, were crushed with what impartial human rights groups described as ‘disproportionate force’.

So many villages have been burned that the UN estimates 700,000 civilians (out of six million Anglophones) have fled to the bush and beyond. UNICEF says more than a million children are out of school. Local civil society groups believe 5,000 people have been killed, although the International Crisis Group, University of Toronto Database of Atrocities and other impartial sources have no accurate casualty numbers. Meanwhile, hundreds of opposition figures are imprisoned without due process.

After the brutal suppression of non-violent Anglophone demonstrations, armed militias emerged, demanding a sovereign country called ‘Ambazonia’. Rights monitors believe all sides behave with impunity, with unarmed civilians caught in the crossfire. The Biya regime held a meeting between the different sides in 2019, but it was dismissed by most Anglophones as a gesture to appease diplomats. This year, the Vatican offered to mediate peace talks, as has Switzerland’s Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, but Biya pursues a military strategy, at huge cost to civilians.

On January 1, the US Senate endorsed the need for targeted sanctions on those implicated in human rights abuses. Yet, the UK and France, Cameroon’s former colonial powers, offer toothless appeals to obey international humanitarian law.

The developed nations must not hold back from criticizing African leaders such as Biya. The tiny, privileged African elite has little concern for its citizens. There will be no justice while the rich world panders to repressive tyrants, giving aid and signing deals with leaders who persecute their populations, trapping people in injustice, poverty and fear. We can hardly be surprised if bright, ambitious Africans leave these countries, heading for opportunity in Europe.

If the death of George Floyd matters, then we must listen to brave black African civil society groups and enforce international human rights laws — such as the ‘responsibility to protect’, a legal doctrine endorsed by Cameroon and most of the international community.

The UK and France must work with partners like the US and Canada to apply diplomatic pressure on the Biya regime. The aim should be inclusive peace talks, mediated by a third party, such as the Swiss and the Vatican.

When my African friends suggest there is a global conspiracy allowing African rulers to commit human rights abuses, I offer a harsher truth; the global north just doesn’t care. Support for Black Lives Matter is meaningless if the wealthy white world averts its eyes from the suffering of persecuted black Africans like those in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions and across the continent.

Source: Spectator.us