11, February 2023

Canada Initiative Offers Opportunity for Southern Cameroons Peace Process 0

Pre-talks between Cameroon’s government and Anglophone separatists, facilitated by Canada, have opened the door to a long-overdue peace process, but Yaoundé has baulked. The government should embrace these talks, while domestic and external actors should put their full weight behind the initiative.

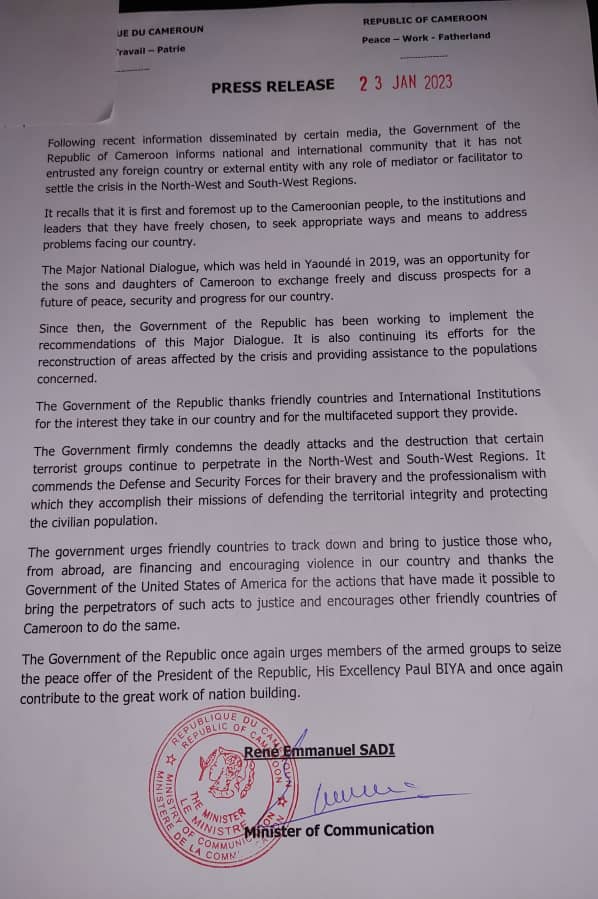

Having cooperated with efforts to bring Cameroon’s government and Anglophone separatists into formal peace talks, Yaoundé should now commit to participate in them. On 20 January, Canada’s foreign minister, Mélanie Joly, announced that the two sides had agreed to start peace negotiations. The announcement raised hopes that there might be a way out of the grinding seven-year conflict in mostly Francophone Cameroon’s two Anglophone regions, the North West and South West. For months, Ottawa had led secret “pre-talks” that seemingly helped the two sides overcome key hurdles to initiating a formal dialogue. Shortly after Joly’s comments, Anglophone leaders issued a joint statement affirming their commitment to participate in negotiations with Canada’s facilitation. But three days later, Cameroon’s government brushed aside Canada’s efforts, denying that it had asked a “foreign party” to broker a resolution to the conflict. The denial revealed deep divisions among top Cameroonian officials and came as a surprise, given Yaoundé’s previous engagement in the Canada-led pre-talks. While this last-minute rejection after months of careful work was a blow to peace efforts, the government can and should correct its course and get the talks on track.

Yaoundé’s brusque dismissal of Canada’s initiative leaves talks in limbo and risks perpetuating, or even escalating, the conflict. Separatist militias immediately responded to the government’s statement with a fresh campaign of violence in the North West and South West regions, erecting roadblocks and firing rocket-propelled grenades at army convoys. Their leaders started discussing the possibility of bringing the militias under a single command or organising joint operations against security forces under the banner of a united Southern Cameroon military front. In Yaoundé, meanwhile, the defence ministry launched a drive to recruit nearly 9,500 new soldiers. Its special forces stepped up patrols in the Anglophone regions and attacked separatist positions.

After seven years of hostilities in the Anglophone regions, the prospect that the parties might miss an opportunity to put hostilities behind them is jarring. The trouble in the North West and South West regions began in October 2016, when lawyers and teachers led protests calling for a two-state federation to preserve the Anglophone legal and educational systems, which they felt were being encroached upon by the Francophone-led central government. The military’s heavy-handed response to peaceful calls for greater autonomy prompted Anglophones to form militias, leading to armed conflict the following year. Since 2017, the fighting has claimed over 6,000 lives in the Anglophone regions and displaced nearly 800,000 people. Making up 60 per cent of the displaced population, women and children face differentiated risks, including gender-based violence and child trafficking. Recent estimates state that the conflict has disrupted the education of over 700,000 children.

Yaoundé has thus far been reluctant to consider a political settlement with the separatists.

Yaoundé has thus far been reluctant to consider a political settlement with the separatists. Previous peace initiatives have foundered. In January 2017, the government suspended negotiations with Anglophone civil society leaders in the city of Bamenda, in the North West region, before arresting them, triggering widespread Anglophone calls for the two regions’ secession. In 2019, President Paul Biya ignored a Swiss offer to facilitate talks, instead organising what purported to be a national conference, but without inviting the most influential separatist leaders. In April 2020, Cameroonian officials began talks with imprisoned separatist leaders, only to suddenly call them off after a second encounter in July of that year. In October 2022, while again rejecting Swiss efforts to push forward with their initiative, the government started low-level consultations with Anglophone leaders in the diaspora. This time around, the separatists’ discretion and clear commitment to finding a resolution persuaded some in Yaoundé to participate at senior levels in pre-talks, with Ottawa’s facilitation, leading observers to believe that the government was ready to take the next step and fully engage in formal talks.

It should. Committing to the Canada-facilitated peace initiative would allow President Biya to change the perception that he has little interest in a political solution, prevent yet another escalation of the conflict and contribute to stabilising the country ahead of elections that are likely to be fraught. The presidential, legislative and local polls due in 2025 are already fuelling familiar political and ethnic tensions that tend to surface during election cycles. Politicians from rival power blocs are positioning themselves to succeed Biya, who has served as president for 40 years and will turn 90 later in February. Cameroon has not seen a single democratic transfer of power since gaining its independence in 1960 and has a history of contested polls, leaving the 2025 elections freighted with uncertainty. Among other reasons for concern, separatist militias forced many Anglophones to boycott votes in 2018 and 2020.

If formal negotiations proceed, they will benefit from good work done in the pre-talk phase. Those pre-talks set as a priority the establishment of confidence-building measures, such as a cessation of hostilities, protection of the right to education and the release of prisoners. Reaching agreement on some or all of these in the next phase of dialogue could ease the suffering of millions of Cameroonians. Building on these achievements, the talks could then turn to issues that will be at the core of any settlement, such as designing a consensual political reconfiguration of the Anglophone regions; reforming the security sector; disarming the rebels; establishing transitional justice mechanisms to address abuses committed over the course of the conflict; and launching economic reconstruction.

Already the Canada-facilitated initiative has yielded clear benefits.

Already the Canada-facilitated initiative has yielded clear benefits. Anglophone faith leaders (Catholics, Presbyterians, Baptists, Muslims and Anglicans), as well as civil society and women’s groups, are more supportive of the prospective Canada talks than of previous initiatives. More critically, the facilitation has also persuaded rival separatist movements to form an orderly bloc. Drawing on earlier efforts by Swiss facilitators, Canada managed to bring together four major separatist groups, with a fifth announcing its commitment to the peace process after Joly’s statement. In the past, separatist groups appeared too divided to reach consensus among themselves. This time around, their unity offers the Cameroonian government a clear counterpart in negotiations.

Key outside interlocutors – including France, Germany, Switzerland, the UK, the U.S. and the Vatican, and multilateral organisations such as the African Union, European Union and UN – should urge Cameroon not to miss this opportunity. They should underscore the benefits that a commitment to formal talks would bring Yaoundé on the security, humanitarian and diplomatic fronts. Should the impasse be overcome, Canada should convene an inclusive discussion among interested Cameroonian parties that would allow them to agree on a negotiation framework that addresses the two sides’ concerns about the agenda for future talks.

To set the talks up for success, Ottawa should seek a public commitment from the Cameroonian government to stick with the process and clarify misconceptions among some Cameroonian parties that Canada seeks a bigger role than to facilitate or is driving toward a particular outcome. For their part, Cameroon’s government and separatist movements should work closely with faith leaders, women’s groups, civil society organisations and politicians to build domestic support for the talks, as suggested by Yaoundé in its 23 January statement. Outside parties should monitor progress closely and provide persistent support, and France should use its close relationship with Cameroon to press for positive momentum.

Progress toward an enduring settlement has not come easily. The tumultuous relationship between Cameroon’s Anglophones and the central government is marked by years of frustration, mistrust and, since 2017, gruesome violence. Unpacking and addressing the two sides’ differences will take time, effort and good faith. The Canada-facilitated process represents a crucial chance to begin this long-overdue work. All those with an interest in the peaceful resolution of Cameroon’s festering Anglophone conflict should do what they can to ensure this opportunity is not squandered.

Culled from International Crisis Group

21, February 2023

Can Nigeria’s Peter Obi ride his newfound momentum all the way to presidency? 0

The rise of Peter Obi in the campaign for Nigeria’s presidential election on February 25 has shaken up the country’s politics, hitherto dominated by two major parties since the end of military rule in 1999. But analysts say that Obi still faces an uphill struggle.

Promising a different way of doing things, Obi hopes to defeat the two favourites and political heavyweights from traditional parties: Atiku Aboubakar of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) and Bola Tinubu of the All Progressives Congress (APC).

With speeches hailed as fresh and unifying – but criticised as populist by his detractors – the 61-year-old businessman has caught the attention of Nigeria’s young population, 60 percent of whom are under the age of 25.

“The current government is in a bad situation, and the way many young people see it is that people like Abubakar and Tinubu are part of the problem,” said Dele Babalola, a Nigeria expert at Canterbury Christ Church University in Kent. “Obe is 61 but he’s the youngest of the candidates [the other two being in their 70s] and a fresh face.”

‘Obidients’

Over the course of the five-month presidential campaign, Obi has gone from minor curiosity to credible candidate, with vast social media support amongst Nigeria’s youth turbocharging his standing. Obi has also enjoyed endorsements from prominent Nigerian figures such as ex-president Olusegun Obasanjo and renowned novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

As Nigeria endures an economic slump and a troubled security situation, Obi’s supporters (nicknamed “Obidients”) see him as an antidote to a political class they accuse of corruption and bad governance.

In this context, Obi has cultivated an image as the picture of integrity and prudence. “I have two children, they are graduates, they have never participated in any public life. I have a son that is going to be 29, 30 soon, he doesn’t own a car because he has to buy his own car, not me,” Obi said in a speech last year to his supporters’ applause.

Obi’s candidacy first emerged in October 2020 as Nigeria saw the #EndSARS protest movement – in which young demonstrators demanded the disbandment of the SARS police unit they accused of violence and saw as benefitting from total immunity, a movement Obi largely supported.

The #EndSARS movement then took its demands further, denouncing corruption and economic inequality. These are burning issues in a country where oil revenues lavishly reward a small proportion of Nigerians while nearly half of the population live below the poverty line, according to the World Bank.

A Nigerian Macron?

Born to Christian parents from the Igbo ethnic group – Nigeria’s third-largest – Obi’s background is a common one in the country’s economic elite: studies in Lagos, at Harvard and at the London School of Economics, followed by a business career including management roles in several Nigerian banks.

As an ex-banker who wants to smash through the old two-party system and reinvigorate his country with a technocratic style of politics, Obi has prompted comparisons to French President Emmanuel Macron – who described himself as “neither left nor right”, created his own political party and swept aside the traditional vehicles of social democracy and conservatism when he took the Élysée Palace and then won a crushing parliamentary majority in 2017.

Obi became leader of Nigeria’s Labour Party last year. Unlike the established British party bearing the same name, it is a rather marginal party – without much political machinery nationally, nor governors with power bases in Nigeria’s provinces.

But “likening Obi to Macron is a mistake”, said Ladipo Adamolekun, a Nigerian public administration expert and Francophile. “Macron created his En Marche! party when France’s traditional parties were already in decline – it’s not like that for Obi.”

And unlike Macron – whose sole political experience when he ran for the Élysée was a short stint as François Hollande’s economy minister – Obi is very far from a political neophyte.

Obi was governor of Anambra, a southern Nigerian state, from 2006 to 2014, before standing as the PDP’s vice-presidential candidate at the last presidential elections in 2019. He has changed his political allegiance four times since 2022, leading to accusations of opportunism.

Obi’s critics also question his probity, since he was mentioned in the Pandora Papers in 2021. However, his supporters say he has proven his integrity with effective governance of Anambra during his eight-year tenure there, which ended with huge savings in the state’s coffers – a compelling argument in an economy burdened by heavy public debt.

Igbo vote ‘won’t be enough’

But for all the hype surrounding Obi, many analysts doubt he can pull off a victory – even despite strong polling figures.

“In reality, a lot of the young people who’ve created all that social media buzz live abroad and can’t vote in Nigeria,” Babalola said. “As for polls, the numbers aren’t as reliable in Africa as they are in Europe,” he added.

Then there is the classic phenomenon of young voters’ poor turnout – which may well be amplified in Nigeria, which tends to have low turnout overall, with just 33 percent going to the polls in the 2019 presidential elections.

Finally, analysts doubt Obi can transcend the issues of ethnicity, religion and regional identity, all of which tend to be crucial factors in Nigerian voters’ choices. “The Igbo vote won’t be enough for Obi to win,” Babalola emphasised, while highlighting the importance of winning votes in the predominantly Muslim north.

Whoever wins at the ballot box, they will face colossal challenges. Nigeria’s economy is Africa’s largest but is troubled by inflation running at more than 20 percent, fuel shortages, a lack of cash during the ill-timed introduction of new bank notes, and an energy crisis causing frequent blackouts.

Public finances are in a bad shape, with debt servicing consuming 41 percent of public spending in 2022. The country’s sovereign ratings downgrade by Moody’s at the end of January is unlikely to help matters.

“As things stand, I doubt the new president will be able to put in place good governance,” said Adamolekun – who favours a “more decentralised federal system” to replace the current political structures.

“The new president will have to accept that the current political system isn’t conducive to the effective governance,” Adamolekun said. “The 1999 constitution was too centralising, especially when it came to the police, and that is a big factor in Nigeria’s security problems.”

Indeed, President Muhammadu Buhari’s last term was plagued by a marked deterioration in Nigeria’s security situation, fuelled by inter-ethnic conflicts, criminal gang activity and jihadism. According to the UN, jihadist violence has killed more than 40,000 people and displaced some 2.2 million in northeastern Nigeria since 2009.

So regardless of whether Obi pulls off an almighty political upset, the new Nigerian president will find plenty of challenges waiting in their inbox.

Source: France 24